Read about and compare the Culture of each Caribbean country.

Date: 2022-01-29

Note: If section exists; includes subsections. The content and structure of each Wikipedia page is different. Some pages captured manually.

The island's cultural history begins with the native Taino, Arawak and Carib. Their artefacts have been found around the island, telling of life before European settlers arrived.[1]

The Anguilla National Trust (ANT) was established in 1988 and opened its offices in 1993 charged with the responsibility of preserving the heritage of the island, including its cultural heritage.[citation needed]

As throughout the Caribbean, holidays are a cultural fixture. Anguilla's most important holidays are of historic as much as cultural importance – particularly the anniversary of the emancipation (previously August Monday in the Park), celebrated as the Summer Festival, or Carnival.[2] British festivities, such as the Queen's Birthday, are also celebrated.[citation needed][3]

Anguillan cuisine is influenced by native Caribbean, African, Spanish, French and English cuisines.[4] Seafood is abundant, including prawns, shrimp, crab, spiny lobster, conch, mahi-mahi, red snapper, marlin and grouper.[4] Salt cod is a staple food eaten on its own and used in stews, casseroles and soups.[4] Livestock is limited due to the small size of the island and people there use poultry, pork, goat and mutton, along with imported beef.[4] Goat is the most commonly eaten meat, used in a variety of dishes.[4] The official national food of Anguilla is pigeon peas and rice.[5]

A significant amount of the island's produce is imported due to limited land suitable for agriculture production; much of the soil is sandy and infertile.[4] Among the agriculture produced in Anguilla includes tomatoes, peppers, limes and other citrus fruits, onion, garlic, squash, pigeon peas and callaloo. Starch staple foods include imported rice and other foods that are imported or locally grown, including yams,[6] sweet potatoes[6] and breadfruit.[4]

The Anguilla National Trust has programmes encouraging Anguillan writers and the preservation of the island's history. In 2015, Where I See The Sun – Contemporary Poetry in Anguilla A New Anthology by Lasana M. Sekou was published by House of Nehesi Publishers.[7] Among the forty three poets in the collection are Rita Celestine-Carty, Bankie Banx, John T. Harrigan, Patricia J. Adams, Fabian Fahie, Dr. Oluwakemi Linda Banks, and Reuel Ben Lewi.[8]

Various Caribbean musical genres are popular on the island, such as reggae, soca and calypso.

Boat racing has deep roots in Anguillan culture and is the national sport.[2] There are regular sailing regattas on national holidays, such as Carnival, which are contested by locally built and designed boats. These boats have names and have sponsors that print their logo on their sails.

As in many other former British colonies, cricket is also a popular sport. Anguilla is the home of Omari Banks, who played for the West Indies Cricket Team, while Cardigan Connor played first-class cricket for English county side Hampshire and was 'chef de mission' (team manager) for Anguilla's Commonwealth Games team in 2002. Other noted players include Chesney Hughes, who played for Derbyshire County Cricket Club in England.

Rugby union is represented in Anguilla by the Anguilla Eels RFC, who were formed in April 2006.[9] The Eels have been finalists in the St. Martin tournament in November 2006 and semi-finalists in 2007, 2008, 2009 and Champions in 2010. The Eels were formed in 2006 by Scottish club national second row Martin Welsh, Club Sponsor and President of the AERFC Ms. Jacquie Ruan, and Canadian standout Scrumhalf Mark Harris (Toronto Scottish RFC).

Anguilla is the birthplace of sprinter Zharnel Hughes who has represented Great Britain since 2015, and England at the 2018 Commonwealth Games. He won the 100 metres at the 2018 European Athletics Championships, the 4 x 100 metres at the same championships, and the 4 x 100 metres for England at the 2018 Commonwealth Games.

Shara Proctor, British Long Jump Silver Medalist in World Championships in Beijing first represented Anguilla in the event until 2010 when she began to represent Great Britain and England. Under the Anguillan Flag she achieved several medals in the NACAC games.

Keith Connor, triple jumper, is also an Anguillan. He represented Great Britain and England and achieved several international titles including Commonwealth and European Games gold medals and an Olympic bronze medal. Keith later became Head Coach of Australia Athletics.

Encyclopedia Britannica – Anguilla was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

The culture is predominantly a mixture of West African and British cultural influences.

Cricket is the national sport. Other popular sports include football, boat racing and surfing. (Antigua Sailing Week attracts locals and visitors from all over the world).

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2010) |

The music of Antigua and Barbuda is largely African in character, and has only felt a limited influence from European styles due to the population of Antigua and Barbuda descending mostly from West Africans who were made slaves by Europeans.[1]

Antigua and Barbuda is a Caribbean nation in the Lesser Antilles island chain. The country is a second home for many of the pan-Caribbean genres of popular music, and has produced stars in calypso, soca, steeldrum, zouk and reggae. Of these, steeldrum and calypso are the most integral parts of modern Antiguan popular music; both styles are imported from the music of Trinidad and Tobago.

Little to no musical research has been undertaken on Antigua and Barbuda other than this. As a result, much knowledge on the topic derives from novels, essays and other secondary sources.[1]The national Carnival held each August commemorates the abolition of slavery in the British West Indies, although on some islands, Carnival may celebrate the coming of Lent. Its festive pageants, shows, contests and other activities are a major tourist attraction.

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (January 2017) |

Antigua and Barbuda cuisine refers to the cuisines of the Caribbean islands Antigua and Barbuda. The national dish is fungie (pronounced "foon-jee") and pepperpot.[2] Fungie is a dish similar to Italian Polenta, made mostly with cornmeal.[2] Other local dishes include ducana, seasoned rice, saltfish and lobster (from Barbuda). There are also local confectionaries which include: sugar cake, fudge, raspberry and tamarind stew and peanut brittle.

Although these foods are indigenous to Antigua and Barbuda and to some other Caribbean countries, the local diet has diversified and now include local dishes of Jamaica, such as jerk meats, or Trinidad, such as Roti, and other Caribbean countries.There are three newspapers: the Antigua Daily Observer, Antigua New Room and The Antiguan Times. The Antigua Observer is the only daily printed newspaper.[3]

The local television channel ABS TV 10 is available (it is the only station that shows exclusively local programs). There are also several local and regional radio stations, such as V2C-AM 620, ZDK-AM 1100, VYBZ-FM 92.9, ZDK-FM 97.1, Observer Radio 91.1 FM, DNECA Radio 90.1 FM, Second Advent Radio 101.5 FM, Abundant Life Radio 103.9 FM, Crusader Radio 107.3 FM, Nice FM 104.3.[3]

Antiguan author Jamaica Kincaid has published over 20 works of literature.[citation needed]

Aruba has a varied culture. According to the Bureau Burgelijke Stand en Bevolkingsregister (BBSB), in 2005 there were ninety-two different nationalities living on the island.[1] Dutch influence can still be seen, as in the celebration of "Sinterklaas" on 5 and 6 December and other national holidays like 27 April, when in Aruba and the rest of the Kingdom of the Netherlands the King's birthday or "Dia di Rey" (Koningsdag) is celebrated.[citation needed]

On 18 March, Aruba celebrates its National Day. Christmas and New Year's Eve are celebrated with the typical music and songs for gaitas for Christmas and the Dande[clarification needed] for New Year, and ayaca, ponche crema, ham, and other typical foods and drinks. On 25 January, Betico Croes' birthday is celebrated. Dia di San Juan is celebrated on 24 June. Besides Christmas, the religious holy days of the Feast of the Ascension and Good Friday are also holidays on the island.

The festival of Carnaval is also an important one in Aruba, as it is in many Caribbean and Latin American countries. Its celebration in Aruba started in the 1950s, influenced by the inhabitants from Venezuela and the nearby islands (Curaçao, St. Vincent, Trinidad, Barbados, St. Maarten, and Anguilla) who came to work for the oil refinery. Over the years, the Carnival Celebration has changed and now starts from the beginning of January until the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday, with a large parade on the last Sunday of the festivities (the Sunday before Ash Wednesday).[2]

Tourism from the United States has recently increased the visibility of American culture on the island, with such celebrations as Halloween in October and Thanksgiving Day in November.[2]

From the beginning of the colonization of the Netherlands until the beginning of the 20th century, the architecture in the most inhabited areas of Aruba was influenced by the Dutch colonial style and also some Spanish elements from the Catholic missionaries present in Aruba who later settled in Venezuela as well. After the boom of the oil industry and the tourist sector in the 20th century the architectural style of the island incorporated a more American and international influence. In addition, elements of the Art Deco style can still be seen in several buildings in San Nicolas. Therefore, it can be said that the island's architecture is a mixture of Spanish, Dutch, American and Caribbean influences.

The culture of the islands is a mixture of African (Afro-Bahamians being the largest ethnicity), British (as the former colonial power) and American (as the dominant country in the region and source of most tourists).[20]

A form of African-based folk magic (obeah) is practised by some Bahamians, mainly in the Family Islands (out-islands) of The Bahamas.[129] The practice of obeah is illegal in The Bahamas and punishable in law.[130]

In the less developed outer islands (or Family Islands), handicrafts include basketry made from palm fronds. This material, commonly called "straw", is plaited into hats and bags that are popular tourist items. Another use is for so-called "Voodoo dolls", even though such dolls are the result of foreign influences and not based in historic fact.[131]

Junkanoo is a traditional Afro-Bahamian street parade of 'rushing', music, dance and art held in Nassau (and a few other settlements) every Boxing Day and New Year's Day. Junkanoo is also used to celebrate other holidays and events such as Emancipation Day.[20]

Regattas are important social events in many family island settlements. They usually feature one or more days of sailing by old-fashioned work boats, as well as an onshore festival.[132]

Many dishes are associated with Bahamian cuisine, which reflects Caribbean, African and European influences. Some settlements have festivals associated with the traditional crop or food of that area, such as the "Pineapple Fest" in Gregory Town, Eleuthera or the "Crab Fest" on Andros. Other significant traditions include story telling.

Bahamians have created a rich literature of poetry, short stories, plays and short fictional works. Common themes in these works are (1) an awareness of change, (2) a striving for sophistication, (3) a search for identity, (4) nostalgia for the old ways and (5) an appreciation of beauty. Some major writers are Susan Wallace, Percival Miller, Robert Johnson, Raymond Brown, O.M. Smith, William Johnson, Eddie Minnis and Winston Saunders.[133][134]

Bahamas culture is rich with beliefs, traditions, folklore and legend. The best-known folklore and legends in The Bahamas include the lusca and chickcharney creatures of Andros, Pretty Molly on Exuma Bahamas and the Lost City of Atlantis on Bimini Bahamas.

The Bahamian flag was adopted in 1973. Its colours symbolise the strength of the Bahamian people; its design reflects aspects of the natural environment (sun and sea) and economic and social development.[13] The flag is a black equilateral triangle against the mast, superimposed on a horizontal background made up of three equal stripes of aquamarine, gold and aquamarine.[13]

The coat of arms of The Bahamas contains a shield with the national symbols as its focal point. The shield is supported by a marlin and a flamingo, which are the national animals of The Bahamas. The flamingo is located on the land, and the marlin on the sea, indicating the geography of the islands.

On top of the shield is a conch shell, which represents the varied marine life of the island chain. The conch shell rests on a helmet. Below this is the actual shield, the main symbol of which is a ship representing the Santa María of Christopher Columbus, shown sailing beneath the sun. Along the bottom, below the shield appears a banner upon which is the national motto:[135]

"Forward, Upward, Onward Together."

The national flower of The Bahamas is the yellow elder, as it is endemic to the Bahama islands and it blooms throughout the year.[136]

Selection of the yellow elder over many other flowers was made through the combined popular vote of members of all four of New Providence's garden clubs of the 1970s—the Nassau Garden Club, the Carver Garden Club, the International Garden Club and the YWCA Garden Club. They reasoned that other flowers grown there—such as the bougainvillea, hibiscus and poinciana—had already been chosen as the national flowers of other countries. The yellow elder, on the other hand, was unclaimed by other countries (although it is now also the national flower of the United States Virgin Islands) and also the yellow elder is native to the family islands.[137]

Sport is a significant part of Bahamian culture. The national sport is cricket, which has been played in The Bahamas from 1846[138]and is the oldest sport played in the country today. The Bahamas Cricket Association was formed in 1936, and from the 1940s to the 1970s, cricket was played amongst many Bahamians. Bahamas is not a part of the West Indies Cricket Board, so players are not eligible to play for the West Indies cricket team. The late 1970s saw the game begin to decline in the country as teachers, who had previously come from the United Kingdom with a passion for cricket, were replaced by teachers who had been trained in the United States. The Bahamian physical education teachers had no knowledge of the game and instead taught track and field, basketball, baseball, softball,[139] volleyball[140] and Association football[141] where primary and high schools compete against each other. Today cricket is still enjoyed by a few locals and immigrants in the country, usually from Jamaica, Guyana, Haiti and Barbados. Cricket is played on Saturdays and Sundays at Windsor Park and Haynes Oval.[142]

The only other sporting event that began before cricket was horse racing, which started in 1796. The most popular spectator sports are those imported from the United States, such as basketball,[143] American football,[144] and baseball,[145] rather than from the British Isles, due to the country's close proximity to the United States, unlike their other Caribbean counterparts, where cricket, rugby, and netball have proven to be more popular.

Over the years American football has become much more popular than soccer, though not implemented in the high school system yet. Leagues for teens and adults have been developed by the Bahamas American Football Federation.[146] However soccer, as it is commonly known in the country, is still a very popular sport amongst high school pupils. Leagues are governed by the Bahamas Football Association. Recently,[when?] the Bahamian government has been working closely with Tottenham Hotspur of London to promote the sport in the country as well as promoting The Bahamas in the European market. In 2013, 'Spurs' became the first Premier League club to play an exhibition match in The Bahamas, facing the Jamaica national team. Joe Lewis, the owner of the club, is based in The Bahamas.[147][148][149]

Other popular sports are swimming,[150] tennis[151] and boxing,[152] where Bahamians have enjoyed some degree of success at the international level. Other sports such as golf,[153] rugby league,[154] rugby union,[155] beach soccer,[156] and netball are considered growing sports. Athletics, commonly known as 'track and field' in the country, is the most successful sport by far amongst Bahamians. Bahamians have a strong tradition in the sprints and jumps. Track and field is probably the most popular spectator sport in the country next to basketball due to their success over the years. Triathlons are gaining popularity in Nassau and the Family Islands.

The Bahamas first participated at the Olympic Games in 1952, and has sent athletes to compete in every Summer Olympic Games since then, except when they participated in the American-led boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics. The nation has never participated in any Winter Olympic Games. Bahamian athletes have won a total of sixteen medals, all in athletics and sailing. The Bahamas has won more Olympic medals than any other country with a population under one million. [157]

The Bahamas were hosts of the first men's senior FIFA tournament to be staged in the Caribbean, the 2017 FIFA Beach Soccer World Cup.[158] The Bahamas also hosted the first 3 editions of the IAAF World Relays.[159]

Notes are in Wikipedia page.

Barbados is a blend of West African, Portuguese, Creole, Indian and British cultures. Citizens are officially called Barbadians. The term "Bajan" (pronounced BAY-jun) may have come from a localised pronunciation of the word Barbadian, which at times can sound more like "Bar-bajan"; or, more likely, from English bay ("bayling"), Portuguese baiano.

The largest carnival-like cultural event that takes place on the island is the Crop Over festival, which was established in 1974. As in many other Caribbean and Latin American countries, Crop Over is an important event for many people on the island, as well as the thousands of tourists that flock to there to participate in the annual events.[1] The festival includes musical competitions and other traditional activities, and features the majority of the island's homegrown calypso and soca music for the year. The male and female Barbadians who harvested the most sugarcane are crowned as the King and Queen of the crop.[2] Crop Over gets under way at the beginning of July and ends with the costumed parade on Kadooment Day, held on the first Monday of August. New calypso/soca music is usually released and played more frequently from the beginning of May to coincide with the start of the festival.[citation needed]

Bajan cuisine is a mixture of African, Indian, Irish, Creole and British influences. A typical meal consists of a main dish of meat or fish, normally marinated with a mixture of herbs and spices, hot side dishes, and one or more salads. A common Bajan side dish could be pickled cucumber, fish cakes, bake, etc. The meal is usually served with one or more sauces.[3] The national dish of Barbados is cou-cou and flying fish with spicy gravy.[4] Another traditional meal is pudding and souse, a dish of pickled pork with spiced sweet potatoes.[5] A wide variety of seafood and meats are also available.

The Mount Gay Rum visitor's centre in Barbados claims to be the world's oldest remaining rum company, with the earliest confirmed deed from 1703. Cockspur Rum and Malibu are also from the island. Barbados is home to the Banks Barbados Brewery, which brews Banks Beer, a pale lager, as well as Banks Amber Ale.[6] Banks also brews Tiger Malt, a non-alcoholic malted beverage. 10 Saints beer is brewed in Speightstown, St. Peter in Barbados and aged for 90 days in Mount Gay 'Special Reserve' Rum casks. It was first brewed in 2009 and is available in certain Caricom nations.[7]

The music of Barbados includes distinctive national styles of folk and popular music, including elements of Western classical and religious music. The culture of Barbados is a syncretic mix of African and British elements, and the island's music reflects this mix through song types and styles, instrumentation, dances, and aesthetic principles.

Barbadian folk traditions include the Landship movement, which is a satirical, informal organization based on the Royal Navy, tea meetings, tuk bands and numerous traditional songs and dances. In modern Barbados, popular styles include calypso, spouge, contemporary folk and world music. Barbados is, along with Guadeloupe, Martinique, Trinidad, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands, one of the few centres for Caribbean jazz.| Date | English name | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1 January | New Year's Day | |

| 21 January | Errol Barrow Day | A day of recognition for Errol Barrow, recognized as the Father of the Nation since 21 January 1989. |

| March or April | Good Friday | Friday, date varies |

| March or April | Easter Monday | Monday, date varies |

| 28 April | National Heroes' Day | A day of recognition for Barbados's national heroes since 28 April 1998. |

| 1–7 May | Labour Day | First Monday in May, date varies |

| May or June | Whit Monday | Monday, date varies |

| 1 August | Emancipation Day | The date on which slavery was abolished on the island, celebrated since 1 August 1997. |

| 1–7 August | Kadooment Day | Climax of Crop Over celebrations. First Monday in August, date varies |

| 30 November | Independence Day | The anniversary of Barbadian national independence, from the United Kingdom on 30 November 1966. |

| 25 December | Christmas Day | |

| 26 December | Boxing Day |

Encylopedia Britannica- Barbados was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2020) |

Belizean cuisine is an amalgamation of all ethnicities in the nation, and their respectively wide variety of foods. It might best be described as both similar to Mexican/Central American cuisine and Jamaican/Anglo-Caribbean cuisine but very different from these areas as well, with Belizean touches and innovation which have been handed down by generations. All immigrant communities add to the diversity of Belizean food, including the Indian and Chinese communities.

The Belizean diet can be both very modern and traditional. There are no rules. Breakfast typically consists of bread, flour tortillas, or fry jacks (deep fried dough pieces) that are often homemade. Fry jacks are eaten with various cheeses, "fry" beans, various forms of eggs or cereal, along with powdered milk, coffee, or tea. Tacos made from corn or flour tortillas and meat pies can also be consumed for a hearty breakfast from a street vendor. Midday meals are the main meals for Belizeans, usually called "dinner". They vary, from foods such as rice and beans with or without coconut milk, tamales, "panades" (fried maize shells with beans or fish), meat pies, escabeche (onion soup), chimole (soup), caldo, stewed chicken, and garnaches (fried tortillas with beans, cheese, and sauce) to various constituted dinners featuring some type of rice and beans, meat and salad, or coleslaw. Fried "fry" chicken is another common course.

In rural areas, meals are typically simpler than in cities. The Maya use maize, beans, or squash for most meals, and the Garifuna are fond of seafood, cassava (particularly made into cassava bread or ereba), and vegetables. The nation abounds with restaurants and fast food establishments that are fairly affordable. Local fruits are quite common, but raw vegetables from the markets less so. Mealtime is a communion for families and schools and some businesses close at midday for lunch, reopening later in the afternoon.

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2012) |

Bermuda's culture is a mixture of the various sources of its population: Native American, Spanish-Caribbean, English, Irish, and Scots cultures were evident in the 17th century, and became part of the dominant British culture. English is the primary and official language. Due to 160 years of immigration from Portuguese Atlantic islands (primarily the Azores, though also from Madeira and the Cape Verde Islands), a portion of the population also speaks Portuguese. There are strong British influences, together with Afro-Caribbean ones.

The first notable, and historically important, book credited to a Bermudian was The History of Mary Prince, a slave narrative by Mary Prince. It is thought to have contributed to the abolition of slavery in the British Empire. Ernest Graham Ingham, an expatriate author, published his books at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. In the 20th century, numerous books were written and published locally, though few were directed at a wider market than Bermuda. (The latter consisted primarily of scholarly works rather than creative writing). The novelist Brian Burland (1931– 2010) achieved a degree of success and acclaim internationally. More recently, Angela Barry has won critical recognition for her published fiction.

Music and dance are an important part of Bermudian culture. West Indian musicians introduced calypso music when Bermuda's tourist industry was expanded with the increase of visitors brought by post-Second World War aviation. Local icons, The Talbot Brothers, performed calypso music for many decades both in Bermuda and the United States, and appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show. While calypso appealed more to tourists than to the local residents, reggae has been embraced by many Bermudians since the 1970s with the influx of Jamaican immigrants.

Noted Bermudian musicians include operatic tenor Dr. Gary Burgess; jazz pianist Lance Hayward; singer-songwriter and poet, Heather Nova, and her brother Mishka, reggae musician; classical musician and conductor Kenneth Amis; and more recently, dancehall artist Collie Buddz.

The dances of the colourful Gombey dancers, seen at many events, are strongly influenced by African, Caribbean, Native American and British cultural traditions. In summer 2001, they performed at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. These Gombey Dancers continue to showcase their work for locals and visitors during the Harbour Nights festival on Bermuda's Front Street every Wednesday evening (during the summer months) and draw very large crowds.

Bermuda's early literature was limited to the works of non-Bermudian writers commenting on the islands. These included John Smith's The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles (1624), and Edmund Waller's poem, "Battle of the Summer Islands" (1645).[1][2]

Bermuda is the only place name in the New World that is alluded to in the works of Shakespeare; it is mentioned in his play The Tempest, in Act 1, Scene 2, line 230: "the still-vexed Bermoothes", this being a reference to the Bermudas.[citation needed]

Local artwork may be viewed at several galleries around Bermuda, and watercolours painted by local artists are also on sale. Alfred Birdsey was one of the more famous and talented watercolourists; his impressionistic landscapes of Hamilton, St George's, and the surrounding sailboats, homes, and bays of Bermuda, are world-renowned. Hand-carved cedar sculptures are another speciality. One such 7 ft (2.1 m) sculpture, created by Bermudian sculptor Chesley Trott, is installed at the airport's baggage claim area. In 2010, his sculpture We Arrive was unveiled in Barr's Bay Park, overlooking Hamilton Harbour, to commemorate the freeing of slaves in 1835 from the American brig Enterprise.[3]

Local resident Tom Butterfield founded the Masterworks Museum of Bermuda Art in 1986, initially featuring works about Bermuda by artists from other countries. He began with pieces by American artists, such as Winslow Homer, Charles Demuth, and Georgia O'Keeffe, who had lived and worked on Bermuda. He has increasingly supported the development of local artists, arts education, and the arts scene.[4] In 2008, the museum opened its new building, constructed within the Botanical Gardens.[5]

Bermuda hosts an annual international film festival, which shows many independent films. One of the founders is film producer and director Arthur Rankin, Jr., co-founder of the Rankin/Bass production company.[6]

Bermudian model Gina Swainson was crowned "Miss World" in 1979.[7]

Many sports popular today were formalised by British public schools and universities in the 19th century. These schools produced the civil servants and military and naval officers required to build and maintain the British Empire, and team sports were considered a vital tool for training their students to think and act as part of a team. Former public schoolboys continued to pursue these activities, and founded organisations such as the Football Association (FA). Today's association of football with the working classes began in 1885 when the FA changed its rules to allow professional players. The Bermuda national football team managed to qualify to the 2019 CONCACAF Gold Cup, the country's first ever major football competition.

The professionals soon displaced the amateur ex-Public schoolboys. Bermuda's role as the primary Royal Navy base in the Western Hemisphere, with an army garrison to match, ensured that the naval and military officers quickly introduced the newly formalised sports to Bermuda, including cricket, football, rugby football, and even tennis and rowing (rowing did not adapt well from British rivers to the stormy Atlantic. The officers soon switched to sail racing, founding the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club). Once these sports reached Bermuda, they were eagerly adopted by Bermudians.

Bermuda's national cricket team participated in the Cricket World Cup 2007 in the West Indies. Their most famous player is a 130-kilogram (290 lb) police officer named Dwayne Leverock. But India defeated Bermuda and set a record of 413 runs in a One-Day International (ODI). Bermuda were knocked out of the World Cup. Also very well known is David Hemp, a former captain of Glamorgan in English first class cricket. The annual "Cup Match" cricket tournament between rival parishes St George's in the east and Somerset in the west is the occasion for a popular national holiday. This tournament began in 1872 when Captain Moresby of the Royal Navy introduced the game to Bermuda, holding a match at Somerset to mark forty years since the unjust thraldom of slavery. The East End versus West End rivalry resulted from the locations of the St. George's Garrison (the original army headquarters in Bermuda) on Barrack Hill, St. George's, and the Royal Naval Dockyard at Ireland Island. Moresby founded the Somerset Cricket Club which plays the St. George's Cricket Club in this game (the membership of both clubs has long been mostly civilian).[8]

In 2007, Bermuda hosted the 25th PGA Grand Slam of Golf. This 36-hole event was held on 16–17 October 2007, at the Mid Ocean Club in Tucker's Town. This season-ending tournament is limited to four golfers: the winners of the Masters, U.S. Open, The Open Championship and PGA Championship. The event returned to Bermuda in 2008 and 2009. One-armed Bermudian golfer Quinn Talbot was both the United States National Amputee Golf Champion for five successive years and the British World One-Arm Golf Champion.[9]

The Government announced in 2006 that it would provide substantial financial support to Bermuda's cricket and football teams. Football did not become popular with Bermudians 'til after the Second World War, though teams from the various Royal Navy, British Army Bermuda Garrison, and Royal Air Force units of Bermuda had competed annually for the Governor's Cup introduced by Major-General Sir George Mackworth Bullock in 1913. A combined team of the Bermuda Militia Artillery (BMA) and the Bermuda Militia Infantry (BMI) defeated HMS Malabar to win the cup on 21 March 1943, becoming the first team of a locally raised unit to do so, and the third British Army team to do so since 1926.[10] Bermuda's most prominent footballers are Clyde Best, Shaun Goater, Kyle Lightbourne, Reggie Lambe, Sam Nusum and Nahki Wells. In 2006, the Bermuda Hogges were formed as the nation's first professional football team to raise the standard of play for the Bermuda national football team. The team played in the United Soccer Leagues Second Division but folded in 2013.

Sailing, fishing and equestrian sports are popular with both residents and visitors alike. The prestigious Newport–Bermuda Yacht Race is a more than 100-year-old tradition, with boats racing between Newport, Rhode Island and Bermuda. In 2007, the 16th biennial Marion-Bermuda yacht race occurred. A sport unique to Bermuda is racing the Bermuda Fitted Dinghy. International One Design racing also originated in Bermuda.[11] In December 2013, Bermuda's bid to host the 2017 America's Cup was announced.

At the 2004 Summer Olympics, Bermuda competed in sailing, athletics, swimming, diving, triathlon and equestrian events. In those Olympics, Bermuda's Katura Horton-Perinchief made history by becoming the first black female diver to compete in the Olympic Games. Bermuda has had two Olympic medallists, Clarence Hill - who won a bronze medal in boxing - and Flora Duffy, who won a gold medal in triathlon. It is tradition for Bermuda to march in the Opening Ceremony in Bermuda shorts, regardless of the summer or winter Olympic celebration. Bermuda also competes in the biennial Island Games, which it hosted in 2013.

In 1998, Bermuda established its own Basketball Association.[12] Since then, its national team has taken advantage of Bermuda's advanced basketball facilities[13] and competed at the Caribbean Basketball Championship.

The primary language is North American English, although there is a local dialect.[1] Spanish is spoken by Puerto Rican, Dominican and other Hispanic immigrants.

The traditional music of the British Virgin Islands is called fungi after the local cornmeal dish with the same name, often made with okra. The special sound of fungi is due to a unique local fusion between African and European music. It functions as a medium of local history and folklore and is therefore a cherished cultural form of expression that is part of the curriculum in BVI schools.[citation needed] The fungi bands, also called "scratch bands", use instruments ranging from calabash, washboard, bongos and ukulele, to more traditional western instruments like keyboard, banjo, guitar, bass, triangle and saxophone. Apart from being a form of festive dance music, fungi often contains humorous social commentaries, as well as BVI oral history.[2]

Because of its location and climate the British Virgin Islands has long been a haven for sailing enthusiasts. Sailing is regarded as one of the foremost sports in all of the BVI. Calm waters and steady breezes provide some of the best sailing conditions in the Caribbean.[3]

Many sailing events are held in the waters of this country, the largest of which is a week-long series of races called the Spring Regatta, the premier sailing event of the Caribbean, with several races hosted each day. Boats include everything from full-size mono-hull yachts to dinghies. Captains and their crews come from all around the world to attend these races. The Spring Regatta is part race, part party, part festival. The Spring Regatta is normally held during the first week of April.[4]

Since 2009, the BVI have made a name for themselves as a host of international basketball events. The BVI hosted three of the last four events of the Caribbean Basketball Championship (FIBA CBC Championship).[citation needed]

Encyclopedia Britannica - BVI was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Havana  Santiago de Cuba |

1 | Havana | Havana | 2,131,480 |  Camagüey  Holguín | ||||

| 2 | Santiago de Cuba | Santiago de Cuba | 433,581 | ||||||

| 3 | Camagüey | Camagüey | 308,902 | ||||||

| 4 | Holguín | Holguín | 297,433 | ||||||

| 5 | Santa Clara | Villa Clara | 216,854 | ||||||

| 6 | Guantánamo | Guantánamo | 216,003 | ||||||

| 7 | Victoria de Las Tunas | Las Tunas | 173,552 | ||||||

| 8 | Bayamo | Granma | 159,966 | ||||||

| 9 | Cienfuegos | Cienfuegos | 151,838 | ||||||

| 10 | Pinar del Río | Pinar del Río | 145,193 | ||||||

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

Despite the island's relatively small population, the diversity of languages and cultural influences on Curaçao have generated a remarkable literary tradition, primarily in Dutch and Papiamentu. The oral traditions of the Arawak indigenous peoples are lost. West African slaves brought the tales of Anansi, thus forming the basis of Papiamentu literature. The first published work in Papiamentu was a poem by Joseph Sickman Corsen entitled Atardi, published in the La Cruz newspaper in 1905.[citation needed] Throughout Curaçaoan literature, narrative techniques and metaphors best characterized as magic realism tend to predominate. Novelists and poets from Curaçao have contributed to Caribbean and Dutch literature. Best known are Cola Debrot, Frank Martinus Arion, Pierre Lauffer, Elis Juliana, Guillermo Rosario, Boeli van Leeuwen and Tip Marugg.[citation needed]

Local food is called Krioyo (pronounced the same as criollo, the Spanish word for "Creole") and boasts a blend of flavours and techniques best compared to Caribbean cuisine and Latin American cuisine. Dishes common in Curaçao are found in Aruba and Bonaire as well. Popular dishes include: stobá (a stew made with various ingredients such as papaya, beef or goat), Guiambo (soup made from okra and seafood), kadushi (cactus soup), sopi mondongo (intestine soup), funchi (cornmeal paste similar to fufu, ugali and polenta) and a lot of fish and other seafood. The ubiquitous side dish is fried plantain. Local bread rolls are made according to a Portuguese recipe. All around the island, there are snèks which serve local dishes as well as alcoholic drinks in a manner akin to the English public house.[citation needed]

The ubiquitous breakfast dish is pastechi: fried pastry with fillings of cheese, tuna, ham, or ground meat. Around the holiday season special dishes are consumed, such as the hallaca and pekelé, made out of salt cod. At weddings and other special occasions a variety of kos dushi are served: kokada (coconut sweets), ko'i lechi (condensed milk and sugar sweet) and tentalaria (peanut sweets). The Curaçao liqueur was developed here, when a local experimented with the rinds of the local citrus fruit known as laraha. Surinamese, Chinese, Indonesian, Indian and Dutch culinary influences also abound. The island also has a number of Chinese restaurants that serve mainly Indonesian dishes such as satay, nasi goreng and lumpia (which are all Indonesian names for the dishes). Dutch specialties such as croquettes and oliebollen are widely served in homes and restaurants.[citation needed]

In 2004, the Little League Baseball team from Willemstad, Curaçao, won the world title in a game against the United States champion from Thousand Oaks, California. The Willemstad lineup included Jurickson Profar, the standout shortstop prospect who now plays for the San Diego Padres of Major League Baseball, and Jonathan Schoop.[113]

The 2010 documentary film Boys of Summer[114] details Curaçao's Pabao Little League All-Stars winning their country's eighth straight championship at the 2008 Little League World Series, then going on to defeat other teams, including Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, and earning a spot in Williamsport.[115]

The prevailing trade winds and warm water make Curaçao a location for windsurfing.[116][117]

There is warm, clear water around the island. Scuba divers and snorkelers may have visibility up to 30 metres (98 feet) at the Curaçao Underwater Marine Park, which stretches along 20 kilometres (12 miles) of Curaçao's southern coastline.[118]

Curaçao participated in the 2013 CARIFTA Games. Kevin Philbert stood third in the under-20 male Long Jump with a distance of 7.36 metres (24.15 feet). Vanessa Philbert stood second the under-17 female 1,500 metres (4,900 feet) with a time of 4:47.97.[119][120][121][122]

The Curaçao national football team won the 2017 Caribbean Cup by defeating Jamaica in the final, qualifying for the 2017 CONCACAF Gold Cup.[123] They then traveled to Thailand and participated in the 2019 King's Cup for the first time, eventually winning the tournament by beating Vietnam in the final.[124]

Notes in Wikipedia page.

Dominica is home to a wide range of people. Although it was historically occupied by several native tribes, the Arawaks (Tainos) and Carib (Kalinago) tribes occupied it at the time European settlers reached the island. "Massacre" is a name of a river dedicated to the mass murder of the native villagers by English settlers on St. Kitts -the survivors were forced into exile on Dominica.[1] Both the French and British tried to claim the island and imported slaves from Africa for labour. The remaining Caribs now live on a 3,700-acre (15 km2) territory on the east coast of the island. They elect their own chief. This mix of cultures has produced the current culture.[original research?]

Music and dance are important facets of Dominica's culture. The annual independence celebrations display a variety of traditional song and dance. Since 1997, there have also been weeks of Creole festivals, such as "Creole in the Park" and the "World Creole Music Festival".

Dominica gained prominence on the international music stage when in 1973, Gordon Henderson founded the group Exile One and an original musical genre, which he coined "Cadence-lypso". This paved the way for modern Creole music. Other musical genres include "Jing ping" and "Cadence". Jing ping features the accordion and is native to the island. Dominica's music is a mélange of Haitian, Afro-Cuban, African and European traditions. Popular artists over the years include Chubby and the Midnight Groovers, Bells Combo, the Gaylords (Dominican band), WCK, and Triple Kay.

The 11th annual World Creole Music Festival was held in 2007, part of the island's celebration of independence from Great Britain on 3 November. A year-long reunion celebration began in January 2008, marking 30 years of independence.

Dominica is often seen as a society that is migrating from collectivism to that of individualism. The economy is a developing one that previously depended on agriculture. Signs of collectivism are evident in the small towns and villages which are spread across the island.[clarification needed]

The novelist Jean Rhys was born and raised in Dominica. The island is obliquely depicted in her best-known book, Wide Sargasso Sea. Rhys's friend, the political activist and writer Phyllis Shand Allfrey, set her 1954 novel, The Orchid House, in Dominica.

Much of the Walt Disney film Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest (the second in the series, released in 2006), was shot on location on Dominica (though in the film it was known as "Pelegosto", a fictional island), along with some shooting for the third film in the series, At World's End (2007).

Dominica's cuisine is similar to that of other Caribbean islands, particularly Jamaica, Saint Lucia and Trinidad and Tobago. Like other Commonwealth Caribbean islands, Dominicans have developed a distinct twist to their cuisine. Breakfast is an important daily meal, typically including saltfish, dried and salted codfish, and "bakes" (fried dough). Saltfish and bakes are combined for a fast food snack that can be eaten throughout the day; vendors on Dominica's streets sell these snacks to passersby, together with fried chicken, fish and fruit and yogurt "smoothies". Other breakfast meals include cornmeal porridge, which is made with fine cornmeal or polenta, milk or condensed milk, and sugar to sweeten. Traditional British-influenced dishes, such as eggs and toast, are also popular, as are fried fish and plantains.

Common vegetables include plantains, tannias (a root vegetable), sweet potatoes, potatoes, rice and peas. Meat and poultry typically eaten include chicken, beef and fish. These are often prepared in stews with onions, carrots, garlic, ginger and herbs. The vegetables and meat are browned to create a rich dark sauce. Popular meals include rice and peas, brown stew chicken, stew beef, fried and stewed fish, and many different types of hearty fish broths and soups. These are filled with dumplings, carrots and ground provisions.

Cricket is a popular sport on the island, and Dominica competes in test cricket as part of the West Indies cricket team. In West Indies domestic first-class cricket, Dominica participates as part of the Windward Islands cricket team, although they are often considered a part of the Leeward Islands geographically. This is due to being part of the British Windward Islands colony from 1940 until independence; its cricket federation remains a part of the Windward Islands Cricket Board of Control.

On 24 October 2007, the 8,000-seat Windsor cricket stadium was completed with a donation of EC$33 million (US$17 million, €12 million) from the government of the People's Republic of China.

Netball, basketball, rugby, tennis and association football are gaining popularity as well.

International footballer Julian Wade, Dominica's all-time top goal scorer (as of 2021), currently plays for Brechin City F.C. in Scotland.[2]

During the 2014 Winter Olympics, a husband and wife team of Gary di Silvestri and Angela Morrone di Silvestri spent US$175,000 to register as Dominican citizens and enter the 15 km men's and 10 km women's cross-country skiing events, respectively. Angela did not start her race, and Gary pulled out several hundred meters into his race. To date, they are Dominica's only Winter Olympic athletes.[3]

Athlete Jérôme Romain won the bronze medal at the 1995 World Championships in Athletics triple jump competition. He also qualified for the finals at the 1996 Olympic Games; even though he had to pull out due to injury, his 12th position is the best performance of a Dominican ever at the Olympics.

Due to cultural syncretism, the culture and customs of the Dominican people have a European cultural basis, influenced by both African and native Taíno elements, although endogenous elements have emerged within Dominican culture;[1] culturally the Dominican Republic is among the most-European countries in Spanish America, alongside Puerto Rico, Cuba, Central Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay.[1] Spanish institutions in the colonial era were able to predominate in the Dominican culture's making-of as a relative success in the acculturation and cultural assimilation of African slaves diminished African cultural influence in comparison to other Caribbean countries.

Dominican art is perhaps most commonly associated with the bright, vibrant colors and images that are sold in every tourist gift shop across the country. However, the country has a long history of fine art that goes back to the middle of the 1800s when the country became independent and the beginnings of a national art scene emerged.

Historically, the painting of this time were centered around images connected to national independence, historical scenes, portraits but also landscapes and images of still life. Styles of painting ranged between neoclassicism and romanticism. Between 1920 and 1940 the art scene was influenced by styles of realism and impressionism. Dominican artists were focused on breaking from previous, academic styles in order to develop more independent and individual styles.

The 20th century brought many prominent Dominican writers, and saw a general increase in the perception of Dominican literature. Writers such as Juan Bosch (one of the greatest storytellers in Latin America), Pedro Mir (national poet of the Dominican Republic[2][3][4]), Aida Cartagena Portalatin (poetess par excellence who spoke in the Era of Rafael Trujillo), Emilio Rodríguez Demorizi (the most important Dominican historian, with more than 1000 written works[5][6][7][8]), Manuel del Cabral (main Dominican poet featured in black poetry[9][10]), Hector Inchustegui Cabral (considered one of the most prominent voices of the Caribbean social poetry of the twentieth century[11][12][13][14]), Miguel Alfonseca (poet belonging to Generation 60[15][16]), Rene del Risco (acclaimed poet who was a participant in the June 14 Movement[17][18][19]), Mateo Morrison (excellent poet and writer with numerous awards), among many more prolific authors, put the island in one of the most important in Literature in the twentieth century.

New 21st century Dominican writers have not yet achieved the renown of their 20th century counterparts. However, writers such as Frank Báez (won the 2006 Santo Domingo Book Fair First Prize) [20][21] and Junot Díaz (2008 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for his novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao)[22] lead Dominican literature in the 21st century.

The architecture in the Dominican Republic represents a complex blend of diverse cultures. The deep influence of the European colonists is the most evident throughout the country. Characterized by ornate designs and baroque structures, the style can best be seen in the capital city of Santo Domingo, which is home to the first cathedral, castle, monastery, and fortress in all of the Americas, located in the city's Colonial Zone, an area declared as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.[23][24] The designs carry over into the villas and buildings throughout the country. It can also be observed on buildings that contain stucco exteriors, arched doors and windows, and red tiled roofs.

The indigenous peoples of the Dominican Republic have also had a significant influence on the architecture of the country. The Taíno people relied heavily on the mahogany and guano (dried palm tree leaf) to put together crafts, artwork, furniture, and houses. Utilizing mud, thatched roofs, and mahogany trees, they gave buildings and the furniture inside a natural look, seamlessly blending in with the island's surroundings.

Lately, with the rise in tourism and increasing popularity as a Caribbean vacation destination, architects in the Dominican Republic have now begun to incorporate cutting-edge designs that emphasize luxury. In many ways an architectural playground, villas and hotels implement new styles, while offering new takes on the old. This new style is characterized by simplified, angular corners and large windows that blend outdoor and indoor spaces. As with the culture as a whole, contemporary architects embrace the Dominican Republic's rich history and various cultures to create something new. Surveying modern villas, one can find any combination of the three major styles: a villa may contain angular, modernist building construction, Spanish Colonial-style arched windows, and a traditional Taíno hammock in the bedroom balcony.

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

Dominican cuisine is predominantly Spanish, Taíno, and African. The typical cuisine is quite similar to what can be found in other Latin American countries.[25] One breakfast dish consists of eggs and mangú (mashed, boiled plantain). Heartier versions of mangú are accompanied by deep-fried meat (Dominican salami, typically), cheese, or both. Lunch, generally the largest and most important meal of the day, usually consists of rice, meat, beans, and salad. "La Bandera" (literally "The Flag") is the most popular lunch dish; it consists of meat and red beans on white rice. Sancocho is a stew often made with seven varieties of meat.

Meals tend to favor meats and starches over dairy products and vegetables. Many dishes are made with sofrito, which is a mix of local herbs used as a wet rub for meats and sautéed to bring out all of a dish's flavors. Throughout the south-central coast, bulgur, or whole wheat, is a main ingredient in quipes or tipili (bulgur salad). Other favorite Dominican foods include chicharrón, yuca, casabe, pastelitos(empanadas), batata, yam, pasteles en hoja, chimichurris, and tostones.

Some treats Dominicans enjoy are arroz con leche (or arroz con dulce), bizcocho dominicano (lit. Dominican cake), habichuelas con dulce, flan, frío frío (snow cones), dulce de leche, and caña (sugarcane). The beverages Dominicans enjoy are Morir Soñando, rum, beer, Mama Juana,[26] batida (smoothie), jugos naturales (freshly squeezed fruit juices), mabí, coffee, and chaca (also called maiz caqueao/casqueado, maiz con dulce and maiz con leche), the last item being found only in the southern provinces of the country such as San Juan.

Musically, the Dominican Republic is known for the world popular musical style and genre called merengue,[27]: 376–7 a type of lively, fast-paced rhythm and dance music consisting of a tempo of about 120 to 160 beats per minute (though it varies) based on musical elements like drums, brass, chorded instruments, and accordion, as well as some elements unique to the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, such as the tambora and güira.

Its syncopated beats use Latin percussion, brass instruments, bass, and piano or keyboard. Between 1937 and 1950 merengue music was promoted internationally by Dominican groups like Billo's Caracas Boys, Chapuseaux and Damiron "Los Reyes del Merengue," Joseito Mateo, and others. Radio, television, and international media popularized it further. Some well known merengue performers are Wilfrido Vargas, Johnny Ventura, singer-songwriter Los Hermanos Rosario, Juan Luis Guerra, Fernando Villalona, Eddy Herrera, Sergio Vargas, Toño Rosario, Milly Quezada, and Chichí Peralta.

Merengue became popular in the United States, mostly on the East Coast, during the 1980s and 1990s,[27]: 375 when many Dominican artists residing in the U.S. (particularly New York) started performing in the Latin club scene and gained radio airplay. They included Victor Roque y La Gran Manzana, Henry Hierro, Zacarias Ferreira, Aventura, and Milly Jocelyn Y Los Vecinos. The emergence of bachata, along with an increase in the number of Dominicans living among other Latino groups in New York, New Jersey, and Florida, has contributed to Dominican music's overall growth in popularity.[27]: 378

Bachata, a form of music and dance that originated in the countryside and rural marginal neighborhoods of the Dominican Republic, has become quite popular in recent years. Its subjects are often romantic; especially prevalent are tales of heartbreak and sadness. In fact, the original name for the genre was amargue ("bitterness," or "bitter music,"), until the rather ambiguous (and mood-neutral) term bachata became popular. Bachata grew out of, and is still closely related to, the pan-Latin American romantic style called bolero. Over time, it has been influenced by merengue and by a variety of Latin American guitar styles.

Palo is an Afro-Dominican sacred music that can be found throughout the island. The drum and human voice are the principal instruments. Palo is played at religious ceremonies—usually coinciding with saints' religious feast days—as well as for secular parties and special occasions. Its roots are in the Congo region of central-west Africa, but it is mixed with European influences in the melodies.[28]

Salsa music has had a great deal of popularity in the country. During the late 1960s Dominican musicians like Johnny Pacheco, creator of the Fania All Stars, played a significant role in the development and popularization of the genre.

Dominican rock and Reggaeton are also popular. Many, if not the majority, of its performers are based in Santo Domingo and Santiago.

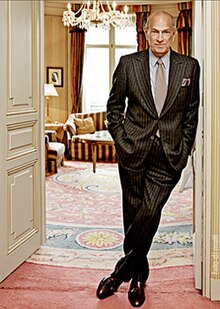

The country boasts one of the ten most important design schools in the region, La Escuela de Diseño de Altos de Chavón, which is making the country a key player in the world of fashion and design. Noted fashion designer Oscar de la Renta was born in the Dominican Republic in 1932, and became a US citizen in 1971. He studied under the leading Spaniard designer Cristóbal Balenciaga and then worked with the house of Lanvin in Paris. By 1963, he had designs bearing his own label. After establishing himself in the US, de la Renta opened boutiques across the country.[clarification needed] His work blends French and Spaniard fashion with American styles.[29][30] Although he settled in New York, de la Renta also marketed his work in Latin America, where it became very popular, and remained active in his native Dominican Republic, where his charitable activities and personal achievements earned him the Juan Pablo Duarte Order of Merit and the Order of Cristóbal Colón.[30] De la Renta died of complications from cancer on October 20, 2014.

Some of the Dominican Republic's important symbols are the flag, the coat of arms, and the national anthem, titled Himno Nacional. The flag has a large white cross that divides it into four quarters. Two quarters are red and two are blue. Red represents the blood shed by the liberators. Blue expresses God's protection over the nation. The white cross symbolizes the struggle of the liberators to bequeath future generations a free nation. An alternative interpretation is that blue represents the ideals of progress and liberty, whereas white symbolizes peace and unity among Dominicans.[31]

In the center of the cross is the Dominican coat of arms, in the same colors as the national flag. The coat of arms pictures a red, white, and blue flag-draped shield with a Bible, a gold cross, and arrows; the shield is surrounded by an olive branch (on the left) and a palm branch (on the right). The Bible traditionally represents the truth and the light. The gold cross symbolizes the redemption from slavery, and the arrows symbolize the noble soldiers and their proud military. A blue ribbon above the shield reads, "Dios, Patria, Libertad" (meaning "God, Fatherland, Liberty"). A red ribbon under the shield reads, "República Dominicana" (meaning "Dominican Republic"). Out of all the flags in the world, the depiction of a Bible is unique to the Dominican flag.

The national flower is the Bayahibe Rose and the national tree is the West Indian Mahogany.[32] The national bird is the Cigua Palmera or Palmchat ("Dulus dominicus").[33]

The Dominican Republic celebrates Dia de la Altagracia on January 21 in honor of its patroness, Duarte's Day on January 26 in honor of one of its founding fathers, Independence Day on February 27, Restoration Day on August 16, Virgen de las Mercedes on September 24, and Constitution Day on November 6.

Baseball is by far the most popular sport in the Dominican Republic.[27]: 59 The Dominican Professional Baseball League consists of six teams. Its season usually begins in October and ends in January. After the United States, the Dominican Republic has the second highest number of Major League Baseball (MLB) players. Ozzie Virgil Sr. became the first Dominican-born player in the MLB on September 23, 1956. Juan Marichal, Pedro Martínez, and Vladimir Guerrero are the only Dominican-born players in the Baseball Hall of Fame.[34] Other notable baseball players born in the Dominican Republic are José Bautista, Adrián Beltré, Juan Soto, Robinson Canó, Rico Carty, Bartolo Colón, Nelson Cruz, Edwin Encarnación, Ubaldo Jiménez, Francisco Liriano, David Ortiz, Plácido Polanco, Albert Pujols, Hanley Ramírez, Manny Ramírez, José Reyes, Alfonso Soriano, Sammy Sosa, Fernando Tatís Jr., and Miguel Tejada. Felipe Alou has also enjoyed success as a manager[35] and Omar Minaya as a general manager. In 2013, the Dominican team went undefeated en route to winning the World Baseball Classic.

In boxing, the country has produced scores of world-class fighters and several world champions,[36] such as Carlos Cruz, his brother Leo, Juan Guzman, and Joan Guzman. Basketball also enjoys a relatively high level of popularity. Tito Horford, his son Al, Felipe Lopez, and Francisco Garcia are among the Dominican-born players currently or formerly in the National Basketball Association (NBA). Olympic gold medalist and world champion hurdler Félix Sánchez hails from the Dominican Republic, as does NFL defensive end Luis Castillo.[37]

Other important sports are volleyball, introduced in 1916 by U.S. Marines and controlled by the Dominican Volleyball Federation, taekwondo, in which Gabriel Mercedes won an Olympic silver medal in 2008, and judo.[38]

Harvey2006 was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

A majority of Grenadians (82%[1]) are descendants of the enslaved Africans.[2][3] Few of the indigenous Carib and Arawak population survived the French purge at Sauteurs.[citation needed] A small percentage of descendants of indentured workers from India were brought to Grenada between 1857 and 1885, predominantly from the states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.[citation needed] Today, Grenadians of Indian descent constitute 2.2% of the population.[2] There is also a small community of French and English descendants.[3] The rest of the population is of mixed descent (13%).[1]

Grenada, like many of the Caribbean islands, is subject to a large amount of out-migration, with a large number of young people seeking more prospects abroad. Popular migration points for Grenadians include more prosperous islands in the Caribbean (such as Barbados), North American Cities (such as New York City, Toronto and Montreal), the United Kingdom (in particular, London and Yorkshire; see Grenadians in the UK) and Australia.[citation needed]

Religion in Grenada (2011 estimate)[4]

Figures are 2011 estimates[4]

English is the country's official language[2] but the main spoken language is either of two creole languages (Grenadian Creole English and, less frequently, Grenadian Creole French) (sometimes called 'patois') which reflects the African, European, and native heritage of the nation. The creoles contain elements from a variety of African languages, French and English. Grenadian Creole French is mainly spoken in smaller rural areas.[citation needed]

Some Hindi/Bhojpuri terms are still spoken amongst the Indo-Grenadian community descendants.[citation needed]

The indigenous languages were Iñeri and Karina (Carib).[citation needed]

cia.gov was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

CIA World Factbook - Grenada was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Encyclopedia Britannica - Grenada was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

For the purposes of local government, Guadeloupe is divided into 32 communes.[1] Each commune has a municipal council and a mayor. Revenues for the communes come from transfers from the French government, and local taxes. Administrative responsibilities at this level include water management, civil register, and municipal police.

| 1 January | New Year's Day |

| Spring | Youman Nabi (Mawlid) |

| 23 February | Republic Day / Mashramani |

| March | Phagwah (Holi) |

| March / April | Good Friday |

| March / April | Easter Sunday |

| March / April | Easter Monday |

| 1 May | Labour Day |

| 5 May | Indian Arrival Day |

| 26 May | Independence Day |

| First Monday in July | CARICOM Day |

| 1 August | Emancipation Day |

| October / November | Diwali |

| 25 December | Christmas |

| 26 or 27 December | Boxing Day |

| Varies | Eid al-Fitr |

| Varies | Eid al-Adha |

Guyana's culture is very similar to that of the English-speaking Caribbean, and has historically been tied to the English-speaking Caribbean as part of the British Empire when it became a possession in the nineteenth century.

Guyanese culture developed as forced and voluntary immigrants adapted and converged with the dominant British culture. Slavery eradicated much of the distinction between differing African cultures, encouraging the adoption of Christianity and the values of British colonists, which laid the foundations of today's Afro-Guyanese culture. Arriving later and under somewhat more favorable circumstances, Indian immigrants were subjected to less assimilation, and preserved more aspects of Indian culture, such as religion, cuisine, music, festivals, and clothing.[1]

Guyana's geographical location, its sparsely populated rain-forest regions, and its substantial Amerindian population differentiate it from English-speaking Caribbean countries. Its blend of the two dominant Indo-Guyanese and Afro-Guyanese cultures gives it similarities to Trinidad and Tobago and Suriname, and distinguishes it from other parts of the Americas. Guyana shares similar interests with the islands in the West Indies, such as food, festive events, music, sports, etc.

Events include Mashramani (Mash), Phagwah (Holi), and Deepavali (Diwali).

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Haiti |

|---|

| History |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Sport |

Haiti has a rich and unique cultural identity, consisting of a blend of traditional French and African customs, mixed with sizable contributions from the Spanish and indigenous Taíno cultures.[1] Haiti's culture is greatly reflected in its paintings, music, and literature. Galleries and museums in the United States and France have exhibited the works of the better-known artists to have come out of Haiti.[2]

Haitian art is distinctive, particularly through its paintings and sculptures.[1][3][4] Brilliant colors, naïve perspectives, and sly humor characterize Haitian art. Frequent subjects in Haitian art include big, delectable foods, lush landscapes, market activities, jungle animals, rituals, dances, and gods. As a result of a deep history and strong African ties, symbols take on great meaning within Haitian society. For example, a rooster often represents Aristide and the red and blue colors of the Haitian flag often represent his Lavalas party.[citation needed] Many artists cluster in 'schools' of painting, such as the Cap-Haïtien school, which features depictions of daily life in the city, the Jacmel School, which reflects the steep mountains and bays of that coastal town, or the Saint-Soleil School, which is characterized by abstracted human forms and is heavily influenced by Vodou symbolism.[citation needed]

In the 1920s the indigéniste movement gained international acclaim, with its expressionist paintings inspired by Haiti's culture and African roots. Notable painters of this movement include Hector Hyppolite, Philomé Oban and Préfète Duffaut.[5] Some notable artists of more recent times include Edouard Duval-Carrié, Frantz Zéphirin, Leroy Exil, Prosper Pierre Louis and Louisiane Saint Fleurant.[5] Sculpture is also practiced in Haiti; noted artists in this form include George Liautaud and Serge Jolimeau.[6]

Haitian music combines a wide range of influences drawn from the many people who have settled here. It reflects French, African and Spanish elements and others who have inhabited the island of Hispaniola, and minor native Taino influences. Styles of music unique to the nation of Haiti include music derived from Vodou ceremonial traditions, Rara parading music, Twoubadou ballads, mini-jazz rock bands, Rasin movement, Hip hop kreyòl, méringue,[7] and compas. Youth attend parties at nightclubs called discos, (pronounced "deece-ko"), and attend Bal. This term is the French word for ball, as in a formal dance.

Compas (konpa) (also known as compas direct in French, or konpa dirèk in creole)[8] is a complex, ever-changing music that arose from African rhythms and European ballroom dancing, mixed with Haiti's bourgeois culture. It is a refined music, with méringue as its basic rhythm. Haiti had no recorded music until 1937 when Jazz Guignard was recorded non-commercially.[9]

Haiti has always been a literary nation that has produced poetry, novels, and plays of international recognition. The French colonial experience established the French language as the venue of culture and prestige, and since then it has dominated the literary circles and the literary production. However, since the 18th century there has been a sustained effort to write in Haitian Creole. The recognition of Creole as an official language has led to an expansion of novels, poems, and plays in Creole.[10] In 1975, Franketienne was the first to break with the French tradition in fiction with the publication of Dezafi, the first novel written entirely in Haitian Creole; the work offers a poetic picture of Haitian life.[11] Other well known Haitian authors include Jean Price-Mars, Jacques Roumain, Marie Vieux-Chauvet, Pierre Clitandre, René Depestre, Edwidge Danticat, Lyonel Trouillot and Dany Laferrière.

Haiti has a small though growing cinema industry. Well-known directors working primarily in documentary film-making include Raoul Peck and Arnold Antonin. Directors producing fictional films include Patricia Benoît, Wilkenson Bruna and Richard Senecal.

Haiti is famous for its creole cuisine (which related to Cajun cuisine), and its soup joumou.[12]

Monuments include the Sans-Souci Palace and the Citadelle Laferrière, inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 1982.[13] Situated in the Northern Massif du Nord, in one of Haiti's National Parks, the structures date from the early 19th century.[14] The buildings were among the first built after Haiti's independence from France. The Citadelle Laferrière, is the largest fortress in the Americas, is located in northern Haiti. It was built between 1805 and 1820 and is today referred to by some Haitians as the eighth wonder of the world.[15]

The Institute for the Protection of National Heritage has preserved 33 historical monuments and the historic center of Cap-Haïtien.[16]

Jacmel, a colonial city that was tentatively accepted as a World Heritage Site, was extensively damaged by the 2010 Haiti earthquake.[14]

The anchor of Christopher Columbus's largest ship, the Santa María now rests in the Musée du Panthéon National Haïtien (MUPANAH), in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.[17]

Haiti is known for its folklore traditions.[18] Much of this is rooted in Haitian Vodou tradition. Belief in zombies is also common.[19] Other folkloric creatures include the lougarou.[19]

The most festive time of the year in Haiti is during Carnival (referred to as Kanaval in Haitian Creole or Mardi Gras) in February.[citation needed] There is music, parade floats, and dancing and singing in the streets. Carnival week is traditionally a time of all-night parties.

Rara is a festival celebrated before Easter. The festival has generated a style of Carnival music.[20][21]

Football (soccer) is the most popular sport in Haiti with hundreds of small football clubs competing at the local level. Basketball and baseball are growing in popularity.[22][23] Stade Sylvio Cator is the multi-purpose stadium in Port-au-Prince, where it is currently used mostly for association football matches that fits a capacity of 10,000 people. In 1974, the Haiti national football team were only the second Caribbean team to make the World Cup (after Cuba's entry in 1938). They lost in the opening qualifying stages against three of the pre-tournament favorites; Italy, Poland, and Argentina. The national team won the 2007 Caribbean Nations Cup.[24]

Haiti has participated in the Olympic Games since the year 1900 and won a number of medals. Haitian footballer Joe Gaetjens played for the United States national team in the 1950 FIFA World Cup, scoring the winning goal in the 1–0 upset of England.[25]

{{cite book}}: External link in |last=| Rank | Name | Parish | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kingston |

1 | Kingston | Kingston | 661,862 |  Montego Bay | ||||

| 2 | Portmore | Saint Catherine | 182,153 | ||||||

| 3 | Spanish Town | Saint Catherine | 147,152 | ||||||

| 4 | Montego Bay | Saint James | 110,115 | ||||||

| 5 | May Pen | Clarendon | 61,548 | ||||||

| 6 | Mandeville | Manchester | 49,695 | ||||||

| 7 | Old Harbour | Saint Catherine | 28,912 | ||||||

| 8 | Savanna-la-Mar | Westmoreland | 22,633 | ||||||

| 9 | Ocho Rios | Saint Ann | 16,671 | ||||||

| 10 | Linstead | Saint Catherine | 15,231 | ||||||

As an overseas département of France, Martinique's culture blends French and Caribbean influences. The city of Saint-Pierre (destroyed by a volcanic eruption of Mount Pelée), was often referred to as the "Paris of the Lesser Antilles". Following traditional French custom, many businesses close at midday to allow a lengthy lunch, then reopen later in the afternoon.

Today, Martinique has a higher standard of living than most other Caribbean countries. French products are easily available, from Chanel fashions to Limoges porcelain. Studying in the métropole (mainland France, especially Paris) is common for young adults. Martinique has been a vacation hotspot for many years, attracting both upper-class French and more budget-conscious travelers.

Martinique has a hybrid cuisine, mixing elements of African, French, Carib Amerindian and Indian subcontinental traditions. One of its most famous dishes is the Colombo (compare kuzhambu (Tamil: குழம்பு) for gravy or broth), a unique curry of chicken (curry chicken), meat or fish with vegetables, spiced with a distinctive masala of Tamil origins, sparked with tamarind, and often containing wine, coconut milk, cassava and rum. A strong tradition of Martiniquan desserts includes cakes made with pineapple, rum, and a wide range of local ingredients.

Sisters Jeanne Nardal and Paulette Nardal were involved in the creation of the Négritude movement. Yva Léro was a writer and painter who co-founded the Women's Union of Martinique. Marie-Magdeleine Carbet wrote with her partner under the pseudonym Carbet.

Aimé Césaire is perhaps Martinique's most famous writer; he was one of the main figures in the Négritude literary movement.[1] René Ménil was a surrealist writer who founded the journal Tropiques with Aimé and Suzanne Césaire and later formulated the concept of Antillanité. Other surrealist writers of that era included Étienne Léro and Jules Monnerot, who co-founded the journal Légitime Défense with Simone Yoyotte and Ménil. Édouard Glissant was later influenced by Césaire and Ménil, and in turn had an influence on Patrick Chamoiseau, who founded the Créolité movement with Raphaël Confiant and Jean Bernabé.[citation needed] Raphaël Confiant was a poetry, prose and non-fiction writer who supports Creole and tries to bring both French and Creole (Martinican and Guadeloupean) together in his work.[2] He is specifically known for his contribution to the Créolité movement.

Frantz Fanon, a prominent critic of colonialism and racism, was also from Martinique.

Martinique has a large popular music industry, which gained in international renown after the success of zouk music in the later 20th century. Zouk's popularity was particularly intense in France, where the genre became an important symbol of identity for Martinique and Guadeloupe.[3] Zouk's origins are in the folk music of Martinique and Guadeloupe, especially Martinican chouval bwa, and Guadeloupan gwo ka. There's also notable influence of the pan-Caribbean calypso tradition and Haitian kompa.

As a part of the French Republic, the French tricolour is in use and La Marseillaise is sung at national French events. When representing Martinique outside of the island for sport and cultural events the civil flag is 'Ipséité’ and the anthem is ‘Lorizon’.[4] Martinique's Civil ensign is the cross of St Michael (White cross with 4 blue quarters with one snake in each), which is the official civil ensign of Martinique (it also used to be the one of Saint Lucia). A coat of arms adaptation of the civil ensign (also called snake flag) is used in an unofficial but formal context such as by the Gendarmerie. The independentists also have their own flag, using a red/black/green colours.

:13 was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (May 2016) |

For more than a decade, George Martin's AIR Montserrat studio played host to recording sessions by many well known rock musicians, including Dire Straits, The Police, Rush, Elton John, Michael Jackson and The Rolling Stones.[1] After the volcanic eruptions of 1995 through 1997, and until his death in 2016, George Martin raised funds to help the victims and families on the island. The first event was a star-studded event at London's Royal Albert Hall in September 1997 (Music for Montserrat) featuring many artists who had previously recorded on the island including Paul McCartney, Mark Knopfler, Elton John, Sting, Phil Collins, Eric Clapton and Midge Ure. The event raised £1.5 million.[2] All the proceeds from the show went towards short-term relief for the islanders.[1]

Martin's second major initiative was to release five hundred limited edition lithographs of his score for the Beatles song "Yesterday". Complete with mistakes and tea stains, the lithographs are numbered and signed by Paul McCartney and Martin. The lithograph sale raised more than US$1.4 million which helped fund the building of a new cultural and community centre for Montserrat and provided a much needed focal point to help the re-generation of the island.[1]

Many albums of note were recorded at AIR Studios, including Rush's Power Windows, Dire Straits' Brothers in Arms; Duran Duran's Seven and the Ragged Tiger, The Police's Synchronicity and Ghost in the Machine (videos for "Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic" and "Spirits in the Material World" were filmed in Montserrat), and Jimmy Buffett's Volcano (named for Soufrière Hills).[1] Ian Anderson (of Jethro Tull) recorded the song "Montserrat" on The Secret Language of Birds in tribute to the volcanic difficulties and feeling among residents of being abandoned by the UK government.

In 2017, Montserrat was used to film much of the 2020 film Wendy.[3]

Montserrat has one national radio station, ZJB. The station offers a wide selection of music and news within the island and also on the internet for Montserratians living overseas.