History of Caribbean Countries from Wikipedia

Read about the History of each Caribbean country.

Date: 2022-01-29

Note: If section exists; includes subsections. The content and structure of each Wikipedia page is different. Some pages captured manually.

Country: Anguilla History

Anguilla was first settled by Indigenous Amerindian peoples who migrated from South America.[1] The earliest Native American artefacts found on Anguilla have been dated to around 1300 BC; remains of settlements date from AD 600.[2][3] There are two known petroglyph sites in Anguilla: Big Spring and Fountain Cavern. The rock ledges of Big Spring contain over 100 petroglyphs (dating back to AD 600-1200), the majority consisting of three indentations that form faces.[4]

Precisely when Anguilla was first seen by Europeans is uncertain: some sources claim that Columbus sighted the island during his second voyage in 1493, while others state that the first European explorer was the French Huguenot nobleman and merchant René Goulaine de Laudonnière in 1564.[3] The Dutch West India Company established a fort on the island in 1631. However, the Company later withdrew after its fort was destroyed by the Spanish in 1633.[5]

Traditional accounts state that Anguilla was first colonised by English settlers from Saint Kitts beginning in 1650.[6][7][8] The settlers focused on planting tobacco, and to a lesser extent cotton.[1] The French temporarily took over the island in 1666 but returned it to English control under the terms of the Treaty of Breda the next year.[1] Major John Scott who visited in September 1667, wrote of leaving the island "in good condition" and noted that in July 1668, "200 or 300 people fled thither in time of war".[9] The French attacked again in 1688, 1745 and 1798, causing much destruction but failing to capture the island.[1][3]

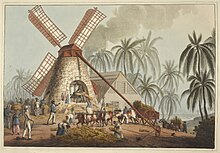

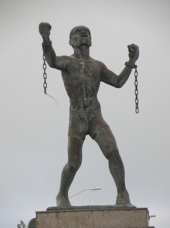

It is likely that the early European settlers brought enslaved Africans with them. Historians confirm that African slaves lived in the region in the early 17th century, such as slaves from Senegal living on St Kitts in the mid 1600s.[10] By 1672 a slave depot existed on the island of Nevis, serving the Leeward Islands.[citation needed] While the time of African arrival in Anguilla is difficult to place precisely, archival evidence indicates a substantial African presence of at least 100 enslaved people by 1683; these seem to have come from Central Africa as well as West Africa.[11] The slaves were forced to work on the sugar plantations which had begun to replace tobacco as Anguilla's main crop.[1] Over time the African slaves and their descendants came to vastly outnumber the white settlers.[1] The African slave trade was eventually terminated within the British Empire in 1807, and slavery outlawed completely in 1834.[1] Many planters subsequently sold up or left the island.[1]

During the early colonial period, Anguilla was administered by the British through Antigua; in 1825, it was placed under the administrative control of nearby Saint Kitts.[3] Anguilla was federated with St Kitts and Nevis in 1882, against the wishes of many Anguillans.[1] Economic stagnation, and the severe effects of several droughts in the 1890s and later the Great Depression of the 1930s led many Anguillans to emigrate for better prospects elsewhere.[1]

Full adult suffrage was introduced to Anguilla in 1952.[1] After a brief period as part of the West Indies Federation (1958–62), the island of Anguilla became part of the associated state of Saint Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla with full internal autonomy in 1967.[12] However many Anguillans had no wish to be a part of this union, and resented the dominance of St Kitts within it. On 30 May 1967 Anguillans forcibly ejected the St Kitts police force from the island and declared their separation from St Kitts following a referendum.[13][1][14] The events, led by Atlin Harrigan[15] and Ronald Webster among others, became known as the Anguillan Revolution; its goal was not independence per se, but rather independence from Saint Kitts and Nevis and a return to being a British colony.

With negotiations failing to break the deadlock, a second referendum confirming Anguillans' desire for separation from St Kitts was held and the Republic of Anguilla was declared unilaterally, with Ronald Webster as president. Efforts by British envoy William Whitlock failed to break the impasse and 300 British troops were subsequently sent in March 1969.[1] British authority was restored, and confirmed by the Anguilla Act of July 1971.[1] In 1980, Anguilla was finally allowed to formally secede from Saint Kitts and Nevis and become a separate British Crown colony (now a British overseas territory).[16][17][12][18][1] Since then, Anguilla has been politically stable, and has seen a large growth in its tourism and offshore financing sectors.[1]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Cite error: The named reference

Encyclopedia Britannica – Anguillawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Caribbean Islands, Sarah Cameron (Footprint Travel Guides), p. 466 (Google Books)

- ^ a b c d "Anguilla's History", The Anguilla House of Assembly Elections, Government of Anguilla, 2007, archived from the original on 13 August 2007, retrieved 9 June 2015

- ^ Source: The Anguilla National Trust - Preservation for Generations.

- ^ Source: Atlas of Mutual Heritage Archived 29 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Martin (1839).

- ^ Charles Prestwood Lucas (2009). A Historical Geography of the British Colonies: The West Indies. General Books LLC. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-4590-0868-7.

- ^ "Encyclopedia Britannica - Anguilla". Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ British Colonial and State Papers 1661–1668, 16 November 1667 and 9 July 1668.

- ^ Hubbard, Vincent K. (2002). A History of St Kitts: The Sweet Trade. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-74760-5.

- ^ Walicek, Don E. (2009). "The Founder Principle and Anguilla's Homestead Society," Gradual Creolization: Studies Celebrating Jacques Arends, ed. by M. van den Berg, H. Cardoso, and R. Selbach. (Creole Language Library Series 34), Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 349–372.

- ^ a b "Encyclopedia Britannica – St Kitts and Nevis". Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Anguilla, 11 July 1967: Separation from St Kitts and Nevis; Peace Committee as Government Direct Democracy (in German)

- ^ David X. Noack: Die abtrünnige Republik Anguilla Archived 17 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, amerika21.de 27 September 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ "Budget Address 2009, "Strengthening the Collective: We are the Solution"" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ Minahan, James (2013). The Complete Guide to National Symbols and Emblems. pp. 656–657. ISBN 9780313344978.

- ^ Hubbard, Vincent (2002). A History of St. Kitts. Macmillan Caribbean. pp. 147–149. ISBN 9780333747605.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Introduction ::Anguillawas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Country: Antigua and Barbuda History

Pre-colonial period

Antigua was first settled by archaic age hunter-gatherer Amerindians called the Ciboney.[1][2][3] Carbon dating has established the earliest settlements started around 3100 BC.[4] They were succeeded by the ceramic age pre-Columbian Arawak-speaking Saladoid people who migrated from the lower Orinoco River.[citation needed] They introduced agriculture, raising, among other crops, the famous Antigua black pineapple (Ananas comosus), corn, sweet potatoes, chiles, guava, tobacco, and cotton.[5] Later on the more bellicose Caribs also settled the island, possibly by force.

European arrival and settlement

Christopher Columbus was the first European to sight the islands in 1493.[2][3] The Spanish did not colonise Antigua until after a combination of European and African diseases, malnutrition, and slavery eventually extirpated most of the native population; smallpox was probably the greatest killer.[6]

The English settled on Antigua in 1632;[3][2] Christopher Codrington settled on Barbuda in 1685.[3][2] Tobacco and then sugar was grown, worked by a large population of slaves from West Africa who soon came to vastly outnumber the European settlers.[2]

Colonial era

The English maintained control of the islands, repulsing an attempted French attack in 1666.[2] The brutal conditions endured by the slaves led to revolts in 1701 and 1729 and a planned revolt in 1736, the last led by Prince Klaas, though it was discovered before it began and the ringleaders were executed.[7] Slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1833, affecting the economy.[3][2] This was exacerbated by natural disasters such as the 1843 earthquake and the 1847 hurricane.[2] Mining occurred on the isle of Redonda, however this ceased in 1929 and the island has since remained uninhabited.[8]

Part of the Leeward Islands colony, Antigua and Barbuda became part of the short-lived West Indies Federation from 1958 to 1962.[3][2] Antigua and Barbuda subsequently became an associated state of the United Kingdom with full internal autonomy on 27 February 1967.[2] The 1970s were dominated by discussions as to the islands' future and the rivalry between Vere Bird of the Antigua and Barbuda Labour Party (ABLP) (Premier from 1967 to 1971 and 1976 to 1981) and the Progressive Labour Movement (PLM) of George Walter (Premier 1971–1976). Eventually Antigua and Barbuda gained full independence on 1 November 1981; Vere Bird became Prime Minister of the new country.[2] The country opted to remain within the Commonwealth, retaining Queen Elizabeth as head of state, with the last Governor, Sir Wilfred Jacobs, as Governor-General.

Independence era

The first two decades of Antigua's independence were dominated politically by the Bird family and the ABLP, with Vere Bird ruling from 1981 to 1994, followed by his son Lester Bird from 1994 to 2004.[2] Though providing a degree of political stability, and boosting tourism to the country, the Bird governments were frequently accused of corruption, cronyism and financial malfeasance.[3][2] Vere Bird Jr., the elder son, was forced to leave the cabinet in 1990 following a scandal in which he was accused of smuggling Israeli weapons to Colombian drug-traffickers.[9][10][3] Another son, Ivor Bird, was convicted of selling cocaine in 1995.[11][12]

In 1995, Hurricane Luis caused severe damage on Barbuda.[13]

The ABLP's dominance of Antiguan politics ended with the 2004 Antiguan general election, which was won by Winston Baldwin Spencer's United Progressive Party (UPP).[2] Winston Baldwin Spencer was Prime Minister of Antigua and Barbuda from 2004 to 2014.[14] However the UPP lost the 2014 Antiguan general election, with the ABLP returning to power under Gaston Browne.[15] ABLP won 15 of the 17 seats in the 2018 snap election under the leadership of incumbent Prime Minister Gaston Browne.[16]

Most of Barbuda was devastated in early September 2017 by Hurricane Irma, which brought winds with speeds reaching 295 km/h (185 mph). The storm damaged or destroyed 95% of the island's buildings and infrastructure, leaving Barbuda "barely habitable" according to Prime Minister Gaston Browne. Nearly everyone on the island was evacuated to Antigua.[17] Amidst the following rebuilding efforts on Barbuda that were estimated to cost at least $100 million,[18] the government announced plans to revoke a century old law of communal land ownership by allowing residents to buy land; a move that has been criticised as promoting "disaster capitalism".[19]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Factbookwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Niddrie, David Lawrence; Momsen, Janet D.; Tolson, Richard. "Antigua and Barbuda". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Antigua and Barbuda : History". The Commonwealth. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Napolitano, Matthew F.; DiNapoli, Robert J.; Stone, Jessica H.; Levin, Maureece J.; Jew, Nicholas P.; Lane, Brian G.; O’Connor, John T.; Fitzpatrick, Scott M. (18 December 2019). "Reevaluating human colonization of the Caribbean using chronometric hygiene and Bayesian modeling". Science Advances. 5 (12): eaar7806. Bibcode:2019SciA....5R7806N. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aar7806. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 6957329. PMID 31976370.

- ^ Duval, D. T. (1996). Saladoid archaeology on St. Vincent, West Indies: results of the 1993/1994 University of Manitoba survey

- ^ Austin Alchon, Suzanne (2003). A pest in the land: new world epidemics in a global perspective. University of New Mexico Press. pp. 62–63. ISBN 0-8263-2871-7.

- ^ "Antigua's Disputed Slave Conspiracy of 1736". Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Kras, Sara Louise (2008). The History of Redonda. Antigua and Barbuda. Cultures of the World. Vol. 26. Marshall Cavendish. p. 18. ISBN 9780761425700.

a cableway using baskets was built to transfer the mined phosphate to a pier for shipping

- ^ "Antiguan Quits in Weapons Scandal". Sun-Journal. 26 April 1990. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ^ "Antigua-Barbuda: Government Finally Orders Probe of Arms Shipment". IPS-Inter Press Service. 25 April 1990.

- ^ Massiah, David (7 May 1995). "Younger Brother of Prime Minister Lester Bird Is Arrested on Cocaine Charges". Associated Press Worldstream. Associated Press.

- ^ Massiah, David (8 May 1995). "Prime Minister Lester Bird Promises No Intervention in Brother's Arrest". Associated Press Worldstream. Associated Press.

- ^ "20th Anniversary of Hurricane Luis". Anumetservice.wordpress.com. 5 September 2015. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ "Caribbean Elections Biography | Winston Baldwin Spencer". www.caribbeanelections.com.

- ^ Charles, Jacqueline. "Browne becomes new prime minister of Antigua, youngest ever". The Miami Herald. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ^ "Speculation about early election in Antigua". Barbados Today. 12 June 2021.

- ^ Panzar, Javier; Willsher, Kim (9 September 2017). "Hurricane Irma leaves Caribbean Islands Devastated". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ John, Tara (11 September 2017). "Hurricane Irma Flattens Barbuda, Leaving Population Stranded". Time. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ Boger, Rebecca; Perdikaris, Sophia (11 February 2019). "After Irma, Disaster Capitalism Threatens Cultural Heritage in Barbuda". NACLA. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

Country: Aruba History

Pre-colonial era

There has been a human presence on Aruba from as early as circa 2000 BC.[1] The first identifiable group are the Arawak Caquetío Amerindians who migrated from South America about 1000 AD.[1][2] Archaeological evidence suggests continuing links between these native Arubans and Amerindian peoples of mainland South America.[3]

Spanish colonization

The first Europeans to visit Aruba were Amerigo Vespucci and Alonso de Ojeda in 1499, who claimed the island for Spain.[1] Both men described Aruba as an "island of giants", remarking on the comparatively large stature of the native Caquetíos.[3] Vespucci returned to Spain with stocks of cotton and brazilwood from the island and described houses built into the ocean.[4] Vespucci and Ojeda's tales spurred interest in Aruba, and the Spanish began colonising the island.[5][6] Alonso de Ojeda was appointed the island's first governor in 1508. From 1513 the Spanish began enslaving the Caquetíos, sending many to a life of forced labour in the mines of Hispaniola.[3][1] The island's low rainfall and arid landscape meant that it was not considered profitable for a slave-based plantation system, so the type of large-scale slavery so common on other Caribbean islands never became established on Aruba.[7]

Early Dutch period

The Netherlands seized Aruba from Spain in 1636 in the course of the Thirty Years' War.[8][1] Peter Stuyvesant, later appointed to New Amsterdam (New York), was the first Dutch governor. Those Arawak who had survived the depredations of the Spanish were allowed to farm and graze livestock, with the Dutch using the island as a source of meat for their other possessions in the Caribbean.[3][1] Aruba's proximity to South America resulted in interactions with the cultures of the coastal areas; for example, architectural similarities can be seen between the 19th-century parts of Oranjestad and the nearby Venezuelan city of Coro in Falcón State.[citation needed] Historically, Dutch was not widely spoken on the island outside of colonial administration; its use increased in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[9] Students on Curaçao, Aruba, and Bonaire were taught predominantly in Spanish until the late 18th century.[10]

During the Napoleonic Wars, the British Empire took control of the island, occupying it between 1806 and 1816, before handing it back to the Dutch as per the terms of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814.[3][8][11][1] Aruba subsequently became part of the Colony of Curaçao and Dependencies along with Bonaire. During the 19th century, an economy based on gold mining, phosphate production and aloe vera plantations developed, but the island remained a relatively poor backwater.[3]

20th and 21st centuries

The first oil refinery in Aruba was built in 1928 by Royal Dutch Shell. The facility was built just to the west of the capital city, Oranjestad, and was commonly called the Eagle. Immediately following that, another refinery was built by Lago Oil and Transport Company, in an area now known as San Nicolas on the east end of Aruba. The refineries processed crude oil from the vast Venezuelan oil fields, bringing greater prosperity to the island.[12] The refinery on Aruba grew to become one of the largest in the world.[3]

During World War II, the Netherlands was occupied by Nazi Germany. In 1940, the oil facilities in Aruba came under the administration of the Dutch government-in-exile in London, causing them to be attacked by the German navy in 1942.[3][13]

In August 1947, Aruba formulated its first Staatsreglement (constitution) for Aruba's status aparte as an autonomous state within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, prompted by the efforts of Henny Eman, a noted Aruban politician. By 1954, the Charter of the Kingdom of the Netherlands was established, providing a framework for relations between Aruba and the rest of the Kingdom.[14] That created the Netherlands Antilles, which united all of the Dutch colonies in the Caribbean into one administrative structure.[15] Many Arubans were unhappy with the arrangement, however, as the new polity was perceived as being dominated by Curaçao.[8]

In 1972, at a conference in Suriname, Betico Croes, a politician from Aruba, proposed the creation of a Dutch Commonwealth of four states: Aruba, the Netherlands, Suriname, and the Netherlands Antilles, each to have its own nationality. Backed by his newly created party, the Movimiento Electoral di Pueblo, Croes sought greater autonomy for Aruba, with the long-term goal of independence, adopting the trappings of an independent state in 1976 with the creation of a flag and national anthem.[3] In March 1977, a referendum was held with the support of the United Nations. 82% of the participants voted for complete independence from the Netherlands.[3][16] Tensions mounted as Croes stepped up the pressure on the Dutch government by organising a general strike in 1977.[3] Croes later met with Dutch Prime Minister Joop den Uyl, with the two sides agreeing to assign the Institute of Social Studies in The Hague to prepare a study for independence, entitled Aruba en Onafhankelijkheid, achtergronden, modaliteiten, en mogelijkheden; een rapport in eerste aanleg (Aruba and independence, backgrounds, modalities, and opportunities; a preliminary report) (1978).[3]

Autonomy

In March 1983, Aruba reached an official agreement within the Kingdom for its independence, to be developed in a series of steps as the Crown granted increasing autonomy. In August 1985, Aruba drafted a constitution that was unanimously approved. On 1 January 1986, after elections were held for its first parliament, Aruba seceded from the Netherlands Antilles, officially becoming a country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, with full independence planned for 1996.[3] However, Croes was seriously injured in a traffic accident in 1985, slipping into a coma. He died in 1986, never seeing the enacting of status aparte for Aruba for which he had worked over many years.[3]

After his death, Croes was proclaimed Libertador di Aruba.[3] Croes' successor, Henny Eman, of the Aruban People's Party (AVP), became the first Prime Minister of Aruba. In 1985, Aruba's oil refinery had closed. It had provided Aruba with 30 percent of its real income and 50 percent of government revenue.[17] The significant blow to the economy led to a push for a dramatic increase in tourism, and that sector has expanded to become the island's largest industry.[3] At a convention in The Hague in 1990, at the request of Aruba's Prime Minister Nelson Oduber, the governments of Aruba, the Netherlands, and the Netherlands Antilles postponed indefinitely Aruba's transition to full independence.[3] The article scheduling Aruba's complete independence was rescinded in 1995, although it was decided that the process could be revived after another referendum.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Aruba History". Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ "Rock Formations". Aruba.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Cite error: The named reference

historiadiaruba1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Sauer; Sauer, Carl Ortwin (30 October 2008). The Early Spanish Main. ISBN 9780521088480.

- ^ Sullivan, Lynne M. (2006). Adventure Guide to Aruba, Bonaire & Curaçao. Edison, NJ: Hunter Publishing, Inc. pp. 57–58. ISBN 9781588435729. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ Sauer, Carl Ortwin (1966). The Early Spanish Main. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 112. ISBN 9780521088480. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "Sitios de Memoria de la Ruta del Esclavo en el Caribe Latino". www.lacult.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Britannicawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Dede pikiña ku su bisiña: Papiamentu-Nederlands en de onverwerkt verleden tijd. van Putte, Florimon., 1999. Zutphen: de Walburg Pers

- ^ Van Putte 1999.

- ^ "British Empire: Caribbean: Aruba". Archived from the original on 9 April 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Albert Gastmann, "Suriname and the Dutch in the Caribbean" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 5, p. 189. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- ^ Central American and Caribbean Air Forces, Daniel Hagedorn, Air Britain (Historians) Ltd., Tonbridge, 1993, p.135, ISBN 0 85130 210 6

- ^ Robbers, Gerhard (2007). Encyclopedia of World Constitutions. Vol. 1. New York City: Facts on File, Inc. p. 649. ISBN 978-0-8160-6078-8. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "Status change means Dutch Antilles no longer exists". BBC News. BBC. 10 October 2010. Archived from the original on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ "BBC News — Aruba profile — Timeline". BBC. 5 November 2013. Archived from the original on 30 August 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ de Cordoba, Jose (23 December 1984). "Aruba Braces for Loss of Refinery". The Washington Post. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

Country: The Bahamas History

Geological history

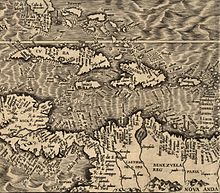

It was generally believed, according to scientists, that the Bahamas were formed in approximately 200 million years ago, when Pangaea started to break apart. In current times, it endures as an archipelago containing over 700 islands and cays, fringed around different coral reefs.[citation needed]

Pre-colonial era

The first inhabitants of the Bahamas were the Taino people, who moved into the uninhabited southern islands from Hispaniola and Cuba around the 800s–1000s AD, having migrated there from South America; they came to be known as the Lucayan people.[1] An estimated 30,000 Lucayans inhabited the Bahamas at the time of Christopher Columbus's arrival in 1492.[2]

Arrival of the Spanish

Columbus's first landfall in what was to Europeans a "New World" was on an island he named San Salvador (known to the Lucayans as Guanahani). Whilst there is a general consensus that this island lay within the Bahamas, precisely which island Columbus landed on is a matter of scholarly debate. Some researchers believe the site to be present-day San Salvador Island (formerly known as Watling's Island), situated in the southeastern Bahamas, whilst an alternative theory holds that Columbus landed to the southeast on Samana Cay, according to calculations made in 1986 by National Geographic writer and editor Joseph Judge, based on Columbus's log. On the landfall island, Columbus made first contact with the Lucayans and exchanged goods with them, claiming the islands for the Crown of Castile, before proceeding to explore the larger isles of the Greater Antilles.[1]

The 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas theoretically divided the new territories between the Kingdom of Castile and the Kingdom of Portugal, placing the Bahamas in the Spanish sphere; however they did little to press their claim on the ground. The Spanish did however exploit the native Lucayan peoples, many of whom were enslaved and sent to Hispaniola for use as forced labour.[1] The slaves suffered harsh conditions and most died from contracting diseases to which they had no immunity; half of the Taino died from smallpox alone.[4] As a result of these depredations the population of the Bahamas was severely diminished.[5]

Arrival of the English

The English had expressed an interest in the Bahamas as early as 1629. However, it was not until 1648 that the first English settlers arrived on the islands. Known as the Eleutherian Adventurers and led by William Sayle, they migrated from Bermuda seeking greater religious freedom. These English Puritans established the first permanent European settlement on an island which they named Eleuthera, Greek for freedom. They later settled New Providence, naming it Sayle's Island. Life proved harder than envisaged however, and many – including Sayle – chose to return to Bermuda.[1] To survive, the remaining settlers salvaged goods from wrecks.

In 1670, King Charles II granted the islands to the Lords Proprietors of the Carolinas in North America. They rented the islands from the king with rights of trading, tax, appointing governors, and administering the country from their base on New Providence.[6][1] Piracy and attacks from hostile foreign powers were a constant threat. In 1684, Spanish corsair Juan de Alcon raided the capital Charles Town (later renamed Nassau),[7] and in 1703, a joint Franco-Spanish expedition briefly occupied Nassau during the War of the Spanish Succession.[8][9]

18th century

During proprietary rule, the Bahamas became a haven for pirates, including Blackbeard (circa 1680–1718).[10] To put an end to the "Pirates' republic" and restore orderly government, Britain made the Bahamas a crown colony in 1718, which they dubbed "the Bahama islands" under the royal governorship of Woodes Rogers.[1] After a difficult struggle, he succeeded in suppressing piracy.[11] In 1720, the Spanish attacked Nassau during the War of the Quadruple Alliance. In 1729, a local assembly was established giving a degree of self-governance for British settlers.[1][12] The reforms had been planned by the previous Governor George Phenney and authorised in July 1728.[13]

During the American War of Independence in the late 18th century, the islands became a target for US naval forces. Under the command of Commodore Esek Hopkins, US Marines, the US Navy occupied Nassau in 1776, before being evacuated a few days later. In 1782 a Spanish fleet appeared off the coast of Nassau, and the city surrendered without a fight. Later, in April 1783, on a visit made by Prince William of the United Kingdom (later to become King William IV) to Luis de Unzaga at his residence in the Captaincy General of Havana, they made prisoner exchange agreements and also dealt with the preliminaries of the Treaty of Paris (1783), in which the recently conquered Bahamas would be exchanged for East Florida, which would still have to conquer the city of St. Augustine, Florida in 1784 by order of Luis de Unzaga; after that, also in 1784, the Bahamas would be declared a British colony.[14]

After US independence, the British resettled some 7,300 Loyalists with their African slaves in the Bahamas, including 2,000 from New York[15] and at least 1,033 European, 2,214 African ancestrals and a few Native American Creeks from East Florida. Most of the refugees resettled from New York had fled from other colonies, including West Florida, which the Spanish captured during the war.[16] The government granted land to the planters to help compensate for losses on the continent. These Loyalists, who included Deveaux and also Lord Dunmore, established plantations on several islands and became a political force in the capital.[1] European Americans were outnumbered by the African-American slaves they brought with them, and ethnic Europeans remained a minority in the territory.

19th century

The Slave Trade Act 1807 abolished slave trading to British possessions, including the Bahamas. The United Kingdom pressured other slave-trading countries to also abolish slave-trading, and gave the Royal Navy the right to intercept ships carrying slaves on the high seas.[17][18] Thousands of Africans liberated from slave ships by the Royal Navy were resettled in the Bahamas.

In the 1820s during the period of the Seminole Wars in Florida, hundreds of North American slaves and African Seminoles escaped from Cape Florida to the Bahamas. They settled mostly on northwest Andros Island, where they developed the village of Red Bays. From eyewitness accounts, 300 escaped in a mass flight in 1823, aided by Bahamians in 27 sloops, with others using canoes for the journey. This was commemorated in 2004 by a large sign at Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park.[19][20] Some of their descendants in Red Bays continue African Seminole traditions in basket making and grave marking.[21]

In 1818,[22] the Home Office in London had ruled that "any slave brought to the Bahamas from outside the British West Indies would be manumitted." This led to a total of nearly 300 enslaved people owned by US nationals being freed from 1830 to 1835.[23] The American slave ships Comet and Encomium used in the United States domestic coastwise slave trade, were wrecked off Abaco Island in December 1830 and February 1834, respectively. When wreckers took the masters, passengers and slaves into Nassau, customs officers seized the slaves and British colonial officials freed them, over the protests of the Americans. There were 165 slaves on the Comet and 48 on the Encomium. The United Kingdom finally paid an indemnity to the United States in those two cases in 1855, under the Treaty of Claims of 1853, which settled several compensation cases between the two countries.[24][25]

Slavery was abolished in the British Empire on 1 August 1834.[1] After that British colonial officials freed 78 North American slaves from the Enterprise, which went into Bermuda in 1835; and 38 from the Hermosa, which wrecked off Abaco Island in 1840.[26] The most notable case was that of the Creole in 1841: as a result of a slave revolt on board, the leaders ordered the US brig to Nassau. It was carrying 135 slaves from Virginia destined for sale in New Orleans. The Bahamian officials freed the 128 slaves who chose to stay in the islands. The Creole case has been described as the "most successful slave revolt in U.S. history".[27]

These incidents, in which a total of 447 enslaved people belonging to US nationals were freed from 1830 to 1842, increased tension between the United States and the United Kingdom. They had been co-operating in patrols to suppress the international slave trade. However, worried about the stability of its large domestic slave trade and its value, the United States argued that the United Kingdom should not treat its domestic ships that came to its colonial ports under duress as part of the international trade. The United States worried that the success of the Creole slaves in gaining freedom would encourage more slave revolts on merchant ships.

During the American Civil War of the 1860s, the islands briefly prospered as a focus for blockade runners aiding the Confederate States.[28][29]

Early 20th century

The early decades of the 20th century were ones of hardship for many Bahamians, characterised by a stagnant economy and widespread poverty. Many eked out a living via subsistence agriculture or fishing.[1]

In August 1940, the Duke of Windsor was appointed Governor of the Bahamas. He arrived in the colony with his wife. Although disheartened at the condition of Government House, they "tried to make the best of a bad situation".[30] He did not enjoy the position, and referred to the islands as "a third-class British colony".[31] He opened the small local parliament on 29 October 1940. The couple visited the "Out Islands" that November, on Axel Wenner-Gren's yacht, which caused controversy;[32] the British Foreign Office strenuously objected because they had been advised by United States intelligence that Wenner-Gren was a close friend of the Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring of Nazi Germany.[32][33]

The Duke was praised at the time for his efforts to combat poverty on the islands. A 1991 biography by Philip Ziegler, however, described him as contemptuous of the Bahamians and other non-European peoples of the Empire. He was praised for his resolution of civil unrest over low wages in Nassau in June 1942, when there was a "full-scale riot".[34] Ziegler said that the Duke blamed the trouble on "mischief makers – communists" and "men of Central European Jewish descent, who had secured jobs as a pretext for obtaining a deferment of draft".[35] The Duke resigned from the post on 16 March 1945.[36][37]

Post-Second World War

Modern political development began after the Second World War. The first political parties were formed in the 1950s, split broadly along ethnic lines, with the United Bahamian Party (UBP) representing the English-descended Bahamians (known informally as the "Bay Street Boys")[38] and the Progressive Liberal Party (PLP) representing the Afro-Bahamian majority.[1]

A new constitution granting the Bahamas internal autonomy went into effect on 7 January 1964, with Chief Minister Sir Roland Symonette of the UBP becoming the first Premier.[39]: p.73 [40] In 1967, Lynden Pindling of the PLP became the first black Premier of the Bahamian colony; in 1968, the title of the position was changed to Prime Minister. In 1968, Pindling announced that the Bahamas would seek full independence.[41] A new constitution giving the Bahamas increased control over its own affairs was adopted in 1968.[42] In 1971, the UBP merged with a disaffected faction of the PLP to form a new party, the Free National Movement (FNM), a de-racialised, centre-right party which aimed to counter the growing power of Pindling's PLP.[43]

The British House of Lords voted to give The Bahamas its independence on 22 June 1973.[44] Prince Charles delivered the official documents to Prime Minister Lynden Pindling, officially declaring The Bahamas a fully independent nation on 10 July 1973,[45] and this date is now celebrated as the country's Independence Day.[46] It joined the Commonwealth of Nations on the same day.[47] Sir Milo Butler was appointed the first governor-general of The Bahamas (the official representative of Queen Elizabeth II) shortly after independence.[48]

Post-independence

Shortly after independence, The Bahamas joined the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank on 22 August 1973,[49] and later the United Nations on 18 September 1973.[50]

Politically, the first two decades were dominated by Pindling's PLP, who went on to win a string of electoral victories. Allegations of corruption, links with drug cartels and financial malfeasance within the Bahamian government failed to dent Pindling's popularity. Meanwhile, the economy underwent a dramatic growth period fuelled by the twin pillars of tourism and offshore finance, significantly raising the standard of living on the islands. The Bahamas' booming economy led to it becoming a beacon for immigrants, most notably from Haiti.[1]

In 1992, Pindling was unseated by Hubert Ingraham of the FNM.[39]: p.78 Ingraham went on to win the 1997 Bahamian general election, before being defeated in 2002, when the PLP returned to power under Perry Christie.[39]: p.82 Ingraham returned to power from 2007 to 2012, followed by Christie again from 2012 to 2017. With economic growth faltering, Bahamians re-elected the FNM in 2017, with Hubert Minnis becoming the fourth prime minister.[1]

In September 2019, Hurricane Dorian struck the Abaco Islands and Grand Bahama at Category 5 intensity, devastating the northwestern Bahamas. The storm inflicted at least US$7 billion in damages and killed more than 50 people,[51][52] with 1,300 people still missing.[53]

In September 2021, the ruling Free National Movement lost to the opposition Progressive Liberal Party in a snap election, as the economy struggles to recover from its deepest crash since at least 1971.[54][55] Progressive Liberal Party (PLP) won 32 of the 39 seats in the House of Assembly. Free National Movement (FNM), led by Minnis, took the remaining seats.[56] On 17 September 2021, the chairman of the Progressive Liberal Party (PLP) Phillip “Brave” Davis was sworn in as the new Prime Minister of Bahamas to succeed Hubert Minnis.[57]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Encyclopedia Britannica – The Bahamas". Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ Keegan, William F. (1992). The people who discovered Columbus: the prehistory of the Bahamas. Jay I. Kislak Reference Collection (Library of Congress). Gainesville: University Press of Florida. pp. 25, 54–8, 86, 170–3. ISBN 0-8130-1137-X. OCLC 25317702.

- ^ Markham, Clements R. (1893). The Journal of Christopher Columbus (during His First Voyage, 1492–93). London: The Hakluyt Society. p. 35. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ^ "Schools Grapple With Columbus's Legacy: Intrepid Explorer or Ruthless Conqueror?", Education Week, 9 October 1991

- ^ Dumene, Joanne E. (1990). "Looking for Columbus". Five Hundred Magazine. 2 (1): 11–15. Archived from the original on 19 September 2008.

- ^ "Diocesan History". Anglican Communications Department. 2009. Archived from the original on 5 May 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- ^ Mancke/Shammas p. 255

- ^ Marley (2005), p. 7.

- ^ Marley (1998), p. 226.

- ^ Headlam, Cecil (1930). America and West Indies: July 1716 | British History Online (Vol 29 ed.). London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. pp. 139–159. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ Woodard, Colin (2010). The Republic of Pirates. Harcourt, Inc. pp. 166–168, 262–314. ISBN 978-0-15-603462-3.

- ^ Dwight C. Hart (2004) The Bahamian parliament, 1729–2004: Commemorating the 275th anniversary Jones Publications, p4

- ^ Hart, p8

- ^ Cazorla, Frank, Baena, Rose, Polo, David, Reder Gadow, Marion (2019) The Governor Louis de Unzaga (1717–1793) Pioneer in the birth of the United States and liberalism, Foundation Malaga, pages 21, 154–155, 163–165, 172, 188–191

- ^ Wertenbaker, Thomas Jefferson (1948). Father Knickerbocker Rebels: New York City during the Revolution. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 260.

- ^ Peters, Thelma (October 1961). "The Loyalist Migration from East Florida to the Bahama Islands". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 40 (2): 123–141. JSTOR 30145777. p. 132, 136, 137

- ^ Falola, Toyin; Warnock, Amanda (2007). Encyclopedia of the Middle Passage. Greenwood Press. pp. xxi, xxxiii–xxxiv. ISBN 9780313334801.

- ^ Lovejoy, Paul E. (2000). Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 290. ISBN 0521780128.

- ^ "Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park", Network to Freedom, National Park Service, 2010, accessed 10 April 2013

- ^ Vignoles, Charles Blacker (1823) Observations on the Floridas, New York: E. Bliss & E. White, pp. 135–136

- ^ Howard, R. (2006). "The "Wild Indians" of Andros Island: Black Seminole Legacy in The Bahamas". Journal of Black Studies. 37 (2): 275. doi:10.1177/0021934705280085. S2CID 144613112.

- ^ Appendix: "Brigs Encomium and Enterprise", Register of Debates in Congress, Gales & Seaton, 1837, pp. 251–253. Note: In trying to retrieve North American slaves off the Encomium from colonial officials (who freed them), the US consul in February 1834 was told by the Lieutenant Governor that "he was acting in regard to the slaves under an opinion of 1818 by Sir Christopher Robinson and Lord Gifford to the British Secretary of State".

- ^ Horne, p. 103

- ^ Horne, p. 137

- ^ Register of Debates in Congress, Gales & Seaton, 1837, The section, "Brigs Encomium and Enterprise", has a collection of lengthy correspondence between US (including M. Van Buren), Vail, the US chargé d'affaires in London, and British agents, including Lord Palmerston, sent to the Senate on 13 February 1837, by President Andrew Jackson, as part of the continuing process of seeking compensation.

- ^ Horne, pp. 107–108

- ^ Williams, Michael Paul (11 February 2002). "Brig Creole slaves". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Richmond, Virginia. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ Grand Bahama Island – American Civil War Archived 25 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine The Islands of The Bahamas Official Tourism Site

- ^ Stark, James. Stark's History and Guide to the Bahama Islands (James H. Stark, 1891). pg.93

- ^ Higham, pp. 300–302

- ^ Bloch, Michael (1982). The Duke of Windsor's War, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-77947-8, p. 364.

- ^ a b Higham, pp. 307–309

- ^ Bloch, Michael (1982). The Duke of Windsor's War. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-77947-8, pp. 154–159, 230–233

- ^ Higham, pp. 331–332

- ^ Ziegler, Philip (1991). King Edward VIII: The Official Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-57730-2. pp. 471–472

- ^ Matthew, H. C. G. (September 2004; online edition January 2008) "Edward VIII, later Prince Edward, Duke of Windsor (1894–1972)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31061, retrieved 1 May 2010 (Subscription required)

- ^ Higham, p. 359 places the date of his resignation as 15 March, and that he left on 5 April.

- ^ "Bad News for the Boys". Time Magazine. 20 January 1967. Archived from the original on 4 February 2013.

- ^ a b c Nohlen, D. (2005), Elections in the Americas: A data handbook, Volume I ISBN 978-0-19-928357-6

- ^ "Bahamian Proposes Independence Move". The Washington Post. United Press International. 19 August 1966. p. A20.

- ^ Bigart, Homer (7 January 1968). "Bahamas Will Ask Britain For More Independence". The New York Times. p. 1.

- ^ Armstrong, Stephen V. (28 September 1968). "Britain and Bahamas Agree on Constitution". The Washington Post. p. A13.

- ^ Hughes, C (1981) Race and Politics in the Bahamas ISBN 978-0-312-66136-6

- ^ "British grant independence to Bahamas". The Baltimore Afro-American. 23 June 1973. p. 22.

- ^ "Bahamas gets deed". Chicago Defender. United Press International. 11 July 1973. p. 3.

- ^ "Bahamas Independence Day Holiday". The Official Site of The Bahamas. The Bahamas Ministry of Tourism. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Bahama Independence". Tri-State Defender. Memphis, Tennessee. 14 July 1973. p. 16.

- ^ Ciferri, Alberto (2019). An Overview of Historical and Socio-Economic Evolution in the Americas. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publisher. p. 313. ISBN 978-1-5275-3821-4. OCLC 1113890667.

- ^ "Bahamas Joins IMF, World Bank". The Washington Post. 23 August 1973. p. C2.

- ^ Alden, Robert (19 September 1973). "2 Germanys Join U.N. as Assembly Opens 28th Year". The New York Times. p. 1.

- ^ Fitz-Gibbon, Jorge (5 September 2019). "Hurricane Dorian causes $7B in property damage to Bahamas". New York Post. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ Stelloh, Tim (9 September 2019). "Hurricane Dorian grows deadlier as more fatalities confirmed in Bahamas". NBC News. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ Karimi, Faith; Thornton, Chandler (12 September 2019). "1,300 people are listed as missing nearly 2 weeks after Hurricane Dorian hit the Bahamas". CNN. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "The Bahamas Election Results". www.caribbeanelections.com. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ "Bloomberg". www.bloomberg.com. 17 September 2021.

- ^ "Bahamas Election 2021: PLP election victory confirmed | Loop Caribbean News". Loop News. 20 September 2021.

- ^ McLeod, Sheri-Kae (17 September 2021). "Phillip Davis Sworn in as Prime Minister of Bahamas ". Caribbean News.

Country: Barbados History

Pre-colonial period

Archeological evidence suggests humans may have first settled or visited the island circa 1600 BC.[1][2][3] More permanent Amerindian settlement of Barbados dates to about the 4th to 7th centuries AD, by a group known as the Saladoid-Barrancoid.[4] The two main groups were the Arawaks from South America, who became dominant around 800–1200 AD, and the more war-like Kalinago (Island Caribs) who arrived from South America in the 12th–13th centuries.[1]

European arrival

It is uncertain which European nation arrived first in Barbados, which probably would have been at some point in the 15th century or 16th century. One lesser-known source points to earlier revealed works antedating contemporary sources, indicating it could have been the Spanish.[5] Many, if not most, believe the Portuguese, en route to Brazil,[6][7] were the first Europeans to come upon the island. The island was largely ignored by Europeans, though Spanish slave raiding is thought to have reduced the native population, with many fleeing to other islands.[1][8]

English settlement in the 17th century

The first English ship, which had arrived on 14 May 1625, was captained by John Powell. The first settlement began on 17 February 1627, near what is now Holetown (formerly Jamestown, after King James I of England),[10] by a group led by John Powell's younger brother, Henry, consisting of 80 settlers and 10 English indentured labourers.[11] Some sources state that some Africans were amongst these first settlers.[1]

The settlement was established as a proprietary colony and funded by Sir William Courten, a City of London merchant who acquired the title to Barbados and several other islands. The first colonists were actually tenants, and much of the profits of their labour returned to Courten and his company.[12] Courten's title was later transferred to James Hay, 1st Earl of Carlisle, in what was called the "Great Barbados Robbery".[citation needed] Carlisle then chose as governor Henry Hawley, who established the House of Assembly in 1639, in an effort to appease the planters, who might otherwise have opposed his controversial appointment.[1][13]

In the period 1640–1660, the West Indies attracted over two-thirds of the total number of English emigrants to the Americas. By 1650 there were 44,000 settlers in the West Indies, as compared to 12,000 on the Chesapeake and 23,000 in New England. Most English arrivals were indentured. After five years of labour, they were given "freedom dues" of about £10, usually in goods. Before the mid-1630s, they also received 5 to 10 acres (2 to 4 hectares) of land, but after that time the island filled and there was no more free land. During the Cromwellian era (1650s) this included a large number of prisoners-of-war, vagrants and people who were illicitly kidnapped, who were forcibly transported to the island and sold as servants. These last two groups were predominantly Irish, as several thousand were infamously rounded up by English merchants and sold into servitude in Barbados and other Caribbean islands during this period, a practice that came to be known as being Barbadosed.[13][14] Cultivation of tobacco, cotton, ginger and indigo was thus handled primarily by European indentured labour until the start of the sugar cane industry in the 1640s and the growing reliance on and importation of enslaved Africans.

Parish registers from the 1650s show that for the white population, there were four times as many deaths as marriages. The mainstay of the infant colony's economy was the growth export of tobacco, but tobacco prices eventually fell in the 1630s as Chesapeake production expanded.[13]

Effects of the English Civil War

Around the same time, fighting during the War of the Three Kingdoms and the Interregnum spilled over into Barbados and Barbadian territorial waters. The island was not involved in the war until after the execution of Charles I, when the island's government fell under the control of Royalists (ironically the Governor, Philip Bell, remaining loyal to Parliament while the Barbadian House of Assembly, under the influence of Humphrey Walrond, supported Charles II). To try to bring the recalcitrant colony to heel, the Commonwealth Parliament passed an act on 3 October 1650 prohibiting trade between England and Barbados, and because the island also traded with the Netherlands, further Navigation Acts were passed, prohibiting any but English vessels trading with Dutch colonies. These acts were a precursor to the First Anglo-Dutch War. The Commonwealth of England sent an invasion force under the command of Sir George Ayscue, which arrived in October 1651. Ayscue, with a smaller force that included Scottish prisoners, surprised a larger force of Royalists, but had to resort to spying and diplomacy ultimately. On 11 January 1652, the Royalists in the House of Assembly led by Lord Willoughby surrendered, which marked the end of royalist privateering as a major threat.[15] The conditions of the surrender were incorporated into the Charter of Barbados (Treaty of Oistins), which was signed at the Mermaid's Inn, Oistins, on 17 January 1652.[16]

Irish people in Barbados

Starting with Cromwell, a large percentage of the white labourer population were indentured servants and involuntarily transported people from Ireland. Irish servants in Barbados were often treated poorly, and Barbadian planters gained a reputation for cruelty.[17]: 55 The decreased appeal of an indenture on Barbados, combined with enormous demand for labour caused by sugar cultivation, led to the use of involuntary transportation to Barbados as a punishment for crimes, or for political prisoners, and also to the kidnapping of labourers who were sent to Barbados involuntarily.[17]: 55 Irish indentured servants were a significant portion of the population throughout the period when white servants were used for plantation labour in Barbados, and while a "steady stream" of Irish servants entered the Barbados throughout the seventeenth century, Cromwellian efforts to pacify Ireland created a "veritable tidal wave" of Irish labourers who were sent to Barbados during the 1650s.[17]: 56 Due to inadequate historical records, the total number of Irish labourers sent to Barbados is unknown, and estimates have been "highly contentious".[17]: 56 While one historical source estimated that as many as 50,000 Irish people were transported to either Barbados or Virginia unwillingly during the 1650s, this estimate is "quite likely exaggerated".[17]: 56 Another estimate that 12,000 Irish prisoners had arrived in Barbados by 1655 has been described as "probably exaggerated" by historian Richard B. Sheridan.[18]: 236 According to historian Thomas Bartlett, it is "generally accepted" that approximately 10,000 Irish were sent to the West Indies involuntarily, and approximately 40,000 came as voluntary indentured servants, while many also travelled as voluntary, un-indentured emigrants.[19]: 256

The sugar revolution

The introduction of sugar cane from Dutch Brazil in 1640 completely transformed society, the economy and the physical landscape. Barbados eventually had one of the world's biggest sugar industries.[20] One group instrumental in ensuring the early success of the industry was the Sephardic Jews, who had originally been expelled from the Iberian peninsula, to end up in Dutch Brazil.[20] As the effects of the new crop increased, so did the shift in the ethnic composition of Barbados and surrounding islands.[13] The workable sugar plantation required a large investment and a great deal of heavy labour. At first, Dutch traders supplied the equipment, financing, and enslaved Africans, in addition to transporting most of the sugar to Europe.[13][1] In 1644 the population of Barbados was estimated at 30,000, of which about 800 were of African descent, with the remainder mainly of English descent. These English smallholders were eventually bought out and the island filled up with large sugar plantations worked by enslaved Africans.[1] By 1660 there was near parity with 27,000 blacks and 26,000 whites. By 1666 at least 12,000 white smallholders had been bought out, died, or left the island, many choosing to emigrate to Jamaica or the American Colonies (notably the Carolinas).[1] As a result, Barbados enacted a slave code as a way of legislatively controlling its black enslaved population.[21] The law's text was influential in laws in other colonies.[22]

By 1680 there were 20,000 free whites and 46,000 enslaved Africans;[1] by 1724, there were 18,000 free whites and 55,000 enslaved Africans.[13]

18th and 19th centuries

The harsh conditions endured by the slaves resulted in several planned slave rebellions, the largest of which was Bussa's rebellion in 1816 which was suppressed by British troops.[1] Growing opposition to slavery led to its abolition in the British Empire in 1833.[1] The plantocracy class retained control of political and economic power on the island, with most workers living in relative poverty.[1]

The 1780 hurricane killed over 4,000 people on Barbados.[23][24] In 1854, a cholera epidemic killed over 20,000 inhabitants.[25]

20th century before independence

Deep dissatisfaction with the situation on Barbados led many to emigrate.[1][26] Things came to a head in the 1930s during the Great Depression, as Barbadians began demanding better conditions for workers, the legalisation of trade unions and a widening of the franchise, which at that point was limited to male property owners.[1] As a result of the increasing unrest the British sent a commission, called the West Indies Royal Commission, or Moyne Commission, in 1938, which recommended enacting many of the requested reforms on the islands.[1] As a result, Afro-Barbadians began to play a much more prominent role in the colony's politics, with universal suffrage being introduced in 1950.[1]

Prominent among these early activists was Grantley Herbert Adams, who helped found the Barbados Labour Party (BLP) in 1938.[27] He became the first Premier of Barbados in 1953, followed by fellow BLP-founder Hugh Gordon Cummins from 1958 to 1961. A group of left-leaning politicians who advocated swifter moves to independence broke off from the BLP and founded the Democratic Labour Party (DLP) in 1955.[28][29] The DLP subsequently won the 1961 Barbadian general election and their leader Errol Barrow became premier.

Full internal self-government was enacted in 1961.[1] Barbados joined the short-lived West Indies Federation from 1958 to 1962, later gaining full independence on 30 November 1966.[1] Errol Barrow became the country's first prime minister. Barbados opted to remain within the Commonwealth of Nations.

The effect of independence meant that the Queen of the United Kingdom ceased to have sovereignty over Barbados, but the island chose to remain a constitutional monarchy with Elizabeth II as Queen of Barbados. The Monarch was represented locally by a Governor-General.[30]

Post-independence era

The Barrow government sought to diversify the economy away from agriculture, seeking to boost industry and the tourism sector. Barbados was also at the forefront of regional integration efforts, spearheading the creation of CARIFTA and CARICOM.[1] The DLP lost the 1976 Barbadian general election to the BLP under Tom Adams. Adams adopted a more conservative and strongly pro-Western stance, allowing the Americans to use Barbados as the launchpad for their invasion of Grenada in 1983.[31] Adams died in office in 1985 and was replaced by Harold Bernard St. John; however, St. John lost the 1986 Barbadian general election, which saw the return of the DLP under Errol Barrow, who had been highly critical of the US intervention in Grenada. Barrow, too, died in office, and was replaced by Lloyd Erskine Sandiford, who remained Prime Minister until 1994.

Owen Arthur of the BLP won the 1994 Barbadian general election, remaining Prime Minister until 2008. Arthur was a strong advocate of republicanism, though a planned referendum to replace Queen Elizabeth as Head of State in 2008 never took place.[32] The DLP won the 2008 Barbadian general election, but the new Prime Minister David Thompson died in 2010 and was replaced by Freundel Stuart. The BLP returned to power in 2018 under Mia Mottley, who became Barbados's first female Prime Minister.[33]

Transition to republic

The Government of Barbados announced on 15 September 2020 that it intended to become a republic by 30 November 2021, the 55th anniversary of its independence resulting in the replacement of the hereditary monarch of Barbados with an elected president.[34][35] Barbados would then cease to be a Commonwealth realm, but could maintain membership in the Commonwealth of Nations, like Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago.[36][37][38][39]

On 20 September 2021, just over a full year after the announcement for the transition was made, the Constitution (Amendment) (No. 2) Bill, 2021 was introduced to the Parliament of Barbados. Passed on 6 October, the Bill made amendments to the Constitution of Barbados, introducing the office of the President of Barbados to replace the role of Elizabeth II, Queen of Barbados.[40] The following week, on 12 October 2021, incumbent Governor-General of Barbados Sandra Mason was jointly nominated by the Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition as candidate to be the first President of Barbados,[41] and was subsequently elected on 20 October.[42] Mason took office on 30 November 2021.[43] Prince Charles, who was heir apparent to the Barbadian Crown, attended the swearing-in ceremony in Bridgetown at the invitation of the Government of Barbados.[44]

Queen Elizabeth II sent a message of congratulations to President Mason and the people of Barbados, saying: "As you celebrate this momentous day, I send you and all Barbadians my warmest good wishes for your happiness, peace and prosperity in the future."[45]

A survey was taken between October 23, 2021 and November 10, 2021 by the University of the West Indies that showed 34% of respondents being in favour of transitioning to a republic, while 30% were indifferent. Notably, no overall majority was found in the survey; with 24% not indicating a preference, and the remaining 12% being opposed to the removal of Queen Elizabeth.[46][47]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Encyclopedia Britannica- Barbados". Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Peter Drewett, 1993. "Excavations at Heywoods, Barbados, and the Economic Basis of the Suazoid Period in the Lesser Antilles", Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society 38:113–137.

- ^ Scott M. Fitzpatrick, "A critical approach to c14 dating in the Caribbean", Latin American Antiquity, 17 (4), pp. 389 ff.

- ^ Beckles, Hilary. A History of Barbados: From Amerindian Settlement to Caribbean Single Market (Cambridge University Press, 2007 edition).

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Spanish Mainwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "AXSES Systems Caribbean Inc., The Barbados Tourism Encyclopaedia". Barbados.org. 8 February 2007. Archived from the original on 16 January 2000. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ "History of Barbados". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 13 September 2010. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ Hilary McD. Beckles, A History of Barbados: From Amerindian Settlement to Caribbean Single Market (Cambridge University Press, 2007 edition), pp. 1–6.

- ^ "New Take on George Slept Here". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ Beckles p. 7.

- ^ "Holetown Barbados – Fun Barbados Sights". funbarbados.com. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ William And John Archived 17 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine, 11 January 201, Shipstamps.co.uk

- ^ a b c d e f "Slavery and Economy in Barbados". Archived from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Corish, Patrick J. (12 March 2009). "The Cromwellian Regime, 1650–60". Patrick J. Corish, The Cromwellian Regime, 1650–1660. Oxford University Press. pp. 353–386. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199562527.003.0014. ISBN 978-0-19-956252-7. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Blakemore, Richard J. and Murphy, Elaine. (2018). The British Civil Wars at Sea, 1638–1653. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press. p. 170. ISBN 9781783272297.

- ^ Watson, Karl (5 November 2009). "The Civil War in Barbados". History in-depth. BBC. Archived from the original on 2 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Monahan, Michael J. (2011). The Creolizing Subject: Race, Reason, and the Politics of Purity (1st ed.). Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0823234509.

- ^ Richard B. Sheridan (1974). Sugar and Slavery: An Economic History of the British West Indies, 1623–1775. Canoe Press. ISBN 978-976-8125-13-2. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ Bartlett, Thomas. "'This famous island set in a Virginian sea': Ireland in the British Empire, 1690–1801". In Marshall, P. J.; Low, Alaine; and Louis, William Roger (1998). P. J. Marshall and Alaine Low (eds.). The Oxford History of the British Empire. Volume II: The Eighteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Ali, Arif (1997). Barbados: Just Beyond Your Imagination. Hansib Publishing (Caribbean) Ltd. pp. 46, 48. ISBN 1-870518-54-3.

- ^ Jerome Handler, New West Indian Guide 91 (2017) 30-55

- ^ Sweet Negotiations: Sugar, Slavery, and Plantation Agriculture in Early Barbados Archived 25 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Chapter 6 "The Expansion of Barbados", p. 112

- ^ Orlando Pérez (1970). "Notes on the Tropical Cyclones of Puerto Rico" (PDF). San Juan, Puerto Rico National Weather Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2007.

- ^ Edward N. Rappaport; Jose Fernandez-Partagas; Jack Beven (1997). "The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492–1996". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ^ "Barbados" Archived 29 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Library of Congress Country Studies.

- ^ "Barbados – population". Archived 29 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Library of Congress Country Studies.

- ^ Price, Sanka (10 March 2014). "'Political giant' passes away". Daily Nation. Nation Publishing. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ "The Party". Official Web Site. Democratic Labour Party. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Nohlen, D. (2005) Elections in the Americas: A data handbook, Volume I, p. 85. ISBN 978-0-19-928357-6

- ^ HRM Queen Elizabeth II (2010). "History and present government – Barbados". The Royal Household. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ Carter, Gercine (26 September 2010). "Ex-airport boss recalls Cubana crash". Nation Newspaper. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ Norman 'Gus' Thomas. "Barbados to vote on move to republic". Caribbean Net News. Archived from the original on 28 December 2007.

- ^ "Barbados General Election Results 2018". caribbeanelections.com. Archived from the original on 12 September 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- ^ Yasharoff, Hannah. "Barbados announces plan to remove Queen Elizabeth as head of state next year". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Barbados elects first president, replacing UK Queen as head of state". Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ Team, Caribbean Lifestyle Editorial (15 September 2020). "Barbados to become an Independent Republic in 2021". Caribbean Culture and Lifestyle. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Speare-Cole, Rebecca (16 September 2020). "Barbados to remove Queen as head of state by November 2021". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Madden, Marlon, ed. (17 September 2020). "Wickham predicts Barbados' republic model to mirror Trinidad's". Top Featured Article. Barbados Today. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

As Barbados prepares to ditch the Queen as its Head of State and become a republic, a prominent political scientist is predicting that Prime Minister Mia Mottley will follow the Trinidad and Tobago model. What's more, Peter Wickham has shot down any idea of the Barbados Labour Party administration holding a referendum on the matter, saying that to do so would be a 'mistake'. 'There is no need to and I don't think it makes a lot of sense. We had a situation where since 1999 this [political party] indicated its desire to go in the direction of a republic. The Opposition has always supported it ... So, I think there is enough cohesion in that regard to go with it,' he said.

- ^ "Barbados to remove Queen Elizabeth as head of state". BBC News. 16 September 2020. Archived from the original on 11 March 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ "Barbados Parliament Bills Archive". www.barbadosparliament.com. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ "Letter to the Speaker RE Nomination of Her Excellency Dame Sandra Mason as 1st President of Barbados" (PDF). Parliament of Barbados. 12 October 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ "Barbados just appointed its first president as it becomes a republic". The National. Scotland. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ "In Barbados, parliament votes to amend constitution, paving the way to republican status". ConstitutionNet. 30 September 2021. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ "Barbados becomes a republic and parts ways with the Queen", BBC News

- ^ "A message from The Queen to the President and people of Barbados". The Royal Family. 30 November 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ "Survey shows support for republic". Barbados Today. 21 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ "UWI poll: Republic preferred option". www.nationnews.com. 20 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

Country: Belize History

Early history

The Maya Civilization emerged at least three millennia ago in the lowland area of the Yucatán Peninsula and the highlands to the south, in the area of present-day southeastern Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, and western Honduras. Many aspects of this culture persist in the area, despite nearly 500 years of European domination. Prior to about 2500 BC, some hunting and foraging bands settled in small farming villages; they domesticated crops such as corn, beans, squash, and chili peppers.

A profusion of languages and subcultures developed within the Maya core culture. Between about 2500 BC and 250 AD, the basic institutions of Maya civilization emerged.[1]

Maya civilization

The Maya civilization spread across the territory of present-day Belize around 1500 BC and flourished there until about AD 900. The recorded history of the middle and southern regions focuses on Caracol, an urban political centre that may have supported over 140,000 people.[2][3] North of the Maya Mountains, the most important political centre was Lamanai.[4] In the late Classic Era of Maya civilization (600–1000 AD), an estimated 400,000 to 1,000,000 people inhabited the area of present-day Belize.[1][5]

When Spanish explorers arrived in the 16th century, the area of present-day Belize included three distinct Maya territories:[6]

- Chetumal province, which encompassed the area around Corozal Bay

- Dzuluinicob province, which encompassed the area between the New River and the Sibun River, west to Tipu

- a southern territory controlled by the Manche Ch'ol Maya, encompassing the area between the Monkey River and the Sarstoon River.

Early colonial period (1506–1862)

Spanish conquistadors explored the land and declared it part of the Spanish Empire, but they failed to settle the territory because of its lack of resources and the hostile tribes of the Yucatán.

English pirates sporadically visited the coast of what is now Belize, seeking a sheltered region from which they could attack Spanish ships (see English settlement in Belize) and cut logwood (Haematoxylum campechianum) trees. The first British permanent settlement was founded around 1716 in what became the Belize District,[7] and during the 18th century, established a system using enslaved Africans to cut logwood trees. This yielded a valuable fixing agent for clothing dyes,[8] and was one of the first ways to achieve a fast black before the advent of artificial dyes. The Spanish granted the British settlers the right to occupy the area and cut logwood in exchange for their help suppressing piracy.[1]

The British first appointed a superintendent over the Belize area in 1786. Before then the British government had not recognized the settlement as a colony for fear of provoking a Spanish attack. The delay in government oversight allowed the settlers to establish their own laws and forms of government. During this period, a few successful settlers gained control of the local legislature, known as the Public Meeting, as well as of most of the settlement's land and timber.

Throughout the 18th century, the Spanish attacked Belize every time war broke out with Britain. The Battle of St. George's Caye was the last of such military engagements, in 1798, between a Spanish fleet and a small force of Baymen and their slaves. From 3 to 5 September, the Spaniards tried to force their way through Montego Caye shoal, but were blocked by defenders. Spain's last attempt occurred on 10 September, when the Baymen repelled the Spanish fleet in a short engagement with no known casualties on either side. The anniversary of the battle has been declared a national holiday in Belize and is celebrated to commemorate the "first Belizeans" and the defence of their territory.[9]

As part of the British Empire (1862–1981)

In the early 19th century, the British sought to reform the settlers, threatening to suspend the Public Meeting unless it observed the government's instructions to eliminate slavery outright. After a generation of wrangling, slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1833.[10] As a result of their enslaved Africans' abilities in the work of mahogany extraction, owners in British Honduras were compensated at £53.69 per enslaved African on average, the highest amount paid in any British territory. (This was a form of reparation that was not given to the enslaved Africans at the time, nor since.) [7]

However, the end of slavery did little to change the formerly enslaved Africans' working conditions if they stayed at their trade. A series of institutions restricted the ability of emancipated African individuals to buy land, in a debt-peonage system. Former "extra special" mahogany or logwood cutters undergirded the early ascription of the capacities (and consequently the limitations) of people of African descent in the colony. Because a small elite controlled the settlement's land and commerce, formerly enslaved Africans had little choice but to continue to work in timber cutting.[7]

In 1836, after the emancipation of Central America from Spanish rule, the British claimed the right to administer the region. In 1862, the United Kingdom formally declared it a British Crown Colony, subordinate to Jamaica, and named it British Honduras.[11] Since 1854, the richest inhabitants elected an assembly of notables by censal vote, which was replaced by a legislative council appointed by the British monarchy.[12]

As a colony, Belize began to attract British investors. Among the British firms that dominated the colony in the late 19th century was the Belize Estate and Produce Company, which eventually acquired half of all privately held land and eventually eliminated peonage. Belize Estate's influence accounts in part for the colony's reliance on the mahogany trade throughout the rest of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century.

The Great Depression of the 1930s caused a near-collapse of the colony's economy as British demand for timber plummeted. The effects of widespread unemployment were worsened by a devastating hurricane that struck the colony in 1931. Perceptions of the government's relief effort as inadequate were aggravated by its refusal to legalize labour unions or introduce a minimum wage. Economic conditions improved during World War II, as many Belizean men entered the armed forces or otherwise contributed to the war effort.

Following the war, the colony's economy stagnated. Britain's decision to devalue the British Honduras dollar in 1949 worsened economic conditions and led to the creation of the People's Committee, which demanded independence. The People's Committee's successor, the People's United Party (PUP), sought constitutional reforms that expanded voting rights to all adults. The first election under universal suffrage was held in 1954 and was decisively won by the PUP, beginning a three-decade period in which the PUP dominated the country's politics. Pro-independence activist George Cadle Price became PUP's leader in 1956 and the effective head of government in 1961, a post he would hold under various titles until 1984.

Under a new constitution, Britain granted British Honduras self-government in 1964. On 1 June 1973, British Honduras was officially renamed Belize.[13] Progress toward independence, however, was hampered by a Guatemalan claim to sovereignty over Belizean territory.

Independent Belize (since 1981)

Belize was granted independence on 21 September 1981. Guatemala refused to recognize the new nation because of its longstanding territorial dispute with the British colony, claiming that Belize belonged to Guatemala. About 1,500 British troops remained in Belize to deter any possible incursions.[14]

With Price at the helm, the PUP won all national elections until 1984. In that election, the first national election after independence, the PUP was defeated by the United Democratic Party (UDP). UDP leader Manuel Esquivel replaced Price as prime minister, with Price himself unexpectedly losing his own House seat to a UDP challenger. The PUP under Price returned to power after elections in 1989. The following year the United Kingdom announced that it would end its military involvement in Belize, and the RAF Harrier detachment was withdrawn the same year, having remained stationed in the country continuously since its deployment had become permanent there in 1980. British soldiers were withdrawn in 1994, but the United Kingdom left behind a military training unit to assist with the newly created Belize Defence Force.

The UDP regained power in the 1993 national election, and Esquivel became prime minister for a second time. Soon afterwards, Esquivel announced the suspension of a pact reached with Guatemala during Price's tenure, claiming Price had made too many concessions to gain Guatemalan recognition. The pact may have curtailed the 130-year-old border dispute between the two countries. Border tensions continued into the early 2000s, although the two countries cooperated in other areas.

In 1996, the Belize Barrier Reef, one of the Western Hemipsphere's most pristine ecosystems, was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The PUP won a landslide victory in the 1998 national elections, and PUP leader Said Musa was sworn in as prime minister. In the 2003 elections the PUP maintained its majority, and Musa continued as prime minister. He pledged to improve conditions in the underdeveloped and largely inaccessible southern part of Belize.

In 2005, Belize was the site of unrest caused by discontent with the PUP government, including tax increases in the national budget. On 8 February 2008, Dean Barrow was sworn in as prime minister after his UDP won a landslide victory in general elections. Barrow and the UDP were re-elected in 2012 with a considerably smaller majority. Barrow led the UDP to a third consecutive general election victory in November 2015, increasing the party's number of seats from 17 to 19. However, he stated the election would be his last as party leader and preparations are under way for the party to elect his successor.

On 11 November 2020, the People's United Party (PUP), led by Johnny Briceño, defeated the United Democratic Party (UDP) for the first time since 2003, having won 26 seats out of 31 to form the new government of Belize. Briceño took office as Prime Minister on 12 November.[15]

- ^ a b c Bolland, Nigel (1993). "Belize: Historical Setting" (PDF). In Tim Merrill (ed.). Guyana and Belize: Country Studies. Library of Congress Federal Research Division.

- ^ Houston, Stephen D.; Robertson, J; Stuart, D (2000). "The Language of Classic Maya Inscriptions". Current Anthropology. 41 (3): 321–356. doi:10.1086/300142. ISSN 0011-3204. PMID 10768879. S2CID 741601.